Mining Companies Want Cheap Power; May Lead The Way To Renewable Energy

A key player in moving Interior Alaska off fossil fuels? Multibillion-dollar mining corporations The mining industry’s global quest for c...

A key player in moving Interior Alaska off fossil fuels? Multibillion-dollar mining corporations

The mining industry’s global quest for cheaper, cleaner power could change how thousands of Alaskans get electricity

Highlighted For Easier Reading By The Country Journal

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON

BY: MAX GRAHAM, NORTHERN JOURNAL - MAY 1, 2025

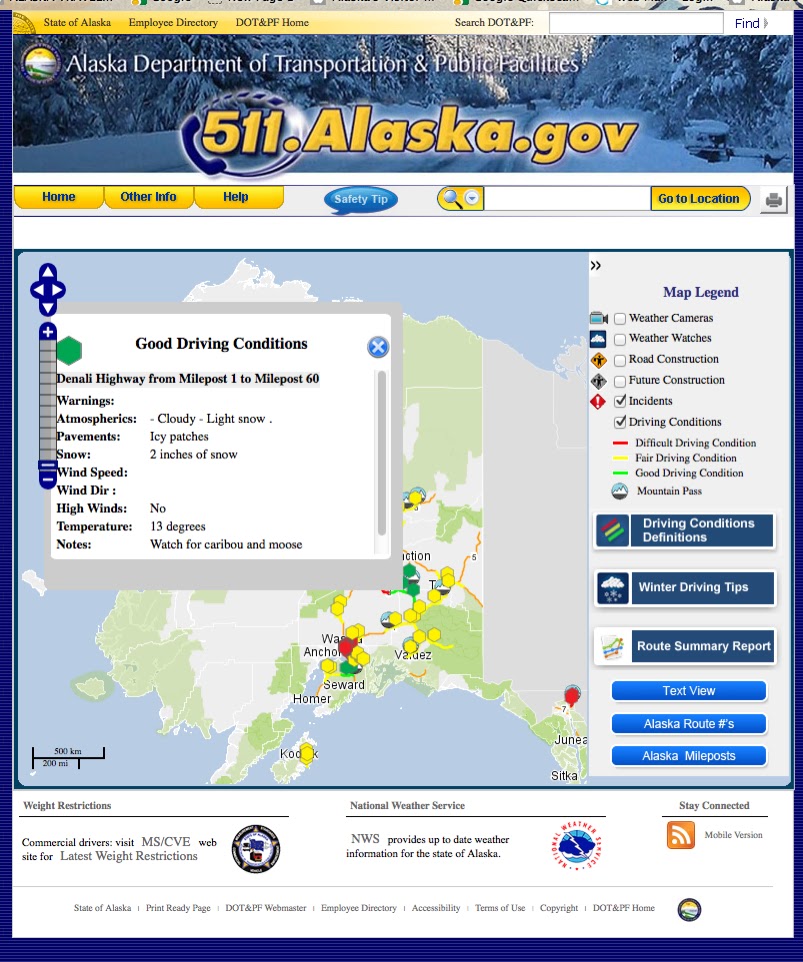

Alaska's largest mine, the Fort Knox gold development outside Fairbanks, consumes $40 million in power each year.

|

| Alaska's largest mine, the Fort Knox gold development outside Fairbanks, consumes $40 million in power each year. (Kinross photo) |

North of Fairbanks, hundreds of workers at Alaska’s biggest gold mine dig up, haul, crush and grind thousands of tons of ore each day, year-round.

The sprawling Fort Knox mine consumes $40 million worth of power every year — more than any other business in the state, and some 16% of the power produced by Fairbanks’ electric utility.

Generating all that energy isn’t cheap. It’s also a huge source of planet-warming greenhouse gases.

Kinross, the global company that owns Fort Knox, operates five other mines, spread across the U.S., South America and Africa. Power at Fort Knox costs more and accounts for more greenhouse gas emissions than each of the company’s other operations, according to Meadow Riedel, a Kinross spokesperson.

Powering Fort Knox generates more greenhouse gas emissions and costs more than at each of the other mines operated by owner Kinross.

The story is similar for Pogo, the Interior’s other major gold mine and the state’s second largest.

In other countries, Kinross and Northern Star, the Australian company that owns Pogo, have spent millions of dollars on solar and wind power to curb carbon emissions and costs at their mines.

In Alaska, they’ve opted for a different approach, at least for now: pushing the cooperatively owned utility that sells them electricity.

Behind the scenes, the two multinational gold mining companies have emerged as key players in the movement to get that utility, Golden Valley Electric Association, to invest more in renewable energy.

Mining exec: Alaska’s pricy, fossil fuel-based power could thwart investment

So far, their efforts have not fully succeeded: The utility has yet to commit to any large new wind or solar projects, and it continues to generate most of its electricity by burning coal and oil.

But the miners’ push underscores how multibillion-dollar resource development corporations have turned into odd bedfellows with Alaska’s climate activists — both calling for the state’s utilities to limit their contributions to global warming.

The corporations, based outside the U.S., have faced social and political pressure from shareholders and government regulators to reduce their environmental impacts. They’ve also seen the cost of solar and wind power fall due to government subsidies and technological improvements, making renewables more competitive with fossil fuels.

New obstacles have arisen, though, as the Trump administration promotes carbon-based fuels and threatens to claw back billions of dollars of clean energy funding.

The stakes are high not only for the mining corporations, but also for Golden Valley Electric Association’s more than 36,000 members — including many residents of Fairbanks, who pay less for electricity as a result of the utility’s massive power sales to the mines.

Renewable energy advocates say replacing fossil fuels with new wind and solar power could lower long-term costs for homes and businesses in Fairbanks and other towns in the Interior. At the same time, a looming shortage of natural gas in Cook Inlet is putting pressure on Golden Valley Electric Association, known as GVEA, to find new ways to generate power.

Hilcorp's Tyonek natural gas platform in Cook Inlet in 2023. A jackup drilling rig is attached to the platform and stands behind it on the latticed legs. (Photo by Nathaniel Herz/Northern Journal)

Offshore oil and gas platforms in Cook Inlet, like this one, once provided a cheap source of energy to Anchorage-area electric utilities, which sold power to the Fairbanks area. But gas has become increasingly expensive to extract from the Inlet, and the utilities have stopped selling power to the Interior and are now looking to import cargoes of LNG to power their generators. (Photo by Nathaniel Herz/Northern Journal)

“The gas crisis and the new administration have really changed how people are approaching this,” said Eleanor Gagnon, who works on energy policy at the Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition. “I think it has the potential to push us forward toward renewables and carbon neutrality — or push us deeper into our fossil fuel track.”

So far, GVEA has taken a cautious approach, with some board members worried that moving too quickly away from conventional energy sources like coal could drive up costs.

But if the utility doesn’t invest in new wind or solar and keeps burning large volumes of fossil fuels, Kinross and Northern Star might be compelled to build their own, independent renewables projects.

That would have consequences across the region: Losing the utility’s two biggest customers could raise electricity costs for thousands of people in Fairbanks, according to Phil Wight, an energy historian at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who is also a GVEA member.

“If GVEA does not commit to building out the next generation of renewables, and doing so relatively soon, the mines may go out and get alternative sources of lower-carbon power — and all GVEA ratepayers would be paying more,” Wight said.

“This is the million dollar question,” Wight added. “Why is GVEA not moving forward with building generation that, everywhere else in the world, utilities are pursuing because it’s cheaper?”

High costs, high emissions

To separate valuable metals from plain rock, mining companies crush and grind ore into tiny pieces — a heavy industrial process that uses loads of electricity.

That means energy is usually one of the top expenses for mining companies. If that energy comes from fossil fuels, it’s also one of companies’ largest sources of planet-heating emissions.

That dynamic is magnified in Alaska, according to company officials.

Fort Knox’s 400,000 tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions in 2023 represent 20% more greenhouse gases per ounce of gold produced when compared to the company’s second highest-emitting mine, in Nevada, corporate disclosures show.

The $40 million in yearly power consumption at Fort Knox represents a disproportionate financial expense, too. In Nevada, where the company operates two mines, electricity costs half as much, according to Riedel, the Kinross spokesperson.

The company’s high costs and emissions in Alaska put Fort Knox at a “disadvantage” in Kinross’s internal decisions about future investments, Riedel said in an emailed statement.

“Kinross Alaska is always competing with other Kinross sites for investment,” she said.

The company has already been working to reduce energy consumption and climate impacts in Alaska as it seeks to eliminate or fully offset carbon pollution at its mines by 2050. Fort Knox has tweaked its ore grinding process to make it more efficient and shortened haul routes to cut down on diesel use, Riedel said.

For now, Kinross isn’t developing any of its own large-scale clean energy projects in Alaska, according to Riedel.

Building renewables at the mine “would be challenging due to Alaska’s expansive geography and extreme climate,” she said.

But Kinross might consider a “smaller scale” development, she said. She would not elaborate on how big of a project the company might build, or on what timeline, though the company spent $55 million on a solar farm at a huge mine in Mauritania.

Wind turbines spin at a development on Kodiak Island. (Photo by Nathaniel Herz/Northern Journal)

Wind turbines spin at a development on Kodiak Island. (Photo by Nathaniel Herz/Northern Journal)

Northern Star, which also has a goal of fully offsetting emissions at its mines by midcentury, has indicated that it might invest in wind power at the Pogo mine, which is about 40 miles northeast of the Interior community of Delta Junction. But the company hasn’t disclosed any concrete plans to do so.

In a corporate report published last year, Northern Star suggested that it expects to develop a project at Pogo in 2025 that would move it toward a companywide goal of lowering emissions by 35% this decade.

A Northern Star spokesperson would not provide details about that project, which is labeled simply in the report as “Pogo GRID 16 MW.” That figure appears to refer to 16 megawatts of power that Pogo draws from the grid.

No major operating mines in Alaska are powered by private solar or wind farms.

At the massive Red Dog zinc mine in Northwest Alaska, which runs on expensive, shipped-in diesel, Vancouver-based Teck Resources said last year that it would install a weather tower to study the potential for generating renewable power.

But those plans fizzled, according to a company spokesperson who declined to comment further.

Frozen funds

Last year, GVEA generated more than 80% of its power from fossil fuels — primarily coal, diesel and naphtha, which is a refined oil product.

The rest comes from a mix of existing wind, solar and hydropower projects.

Until last year, GVEA bought relatively inexpensive gas-fired electricity that other utilities generated in the Anchorage area. But a shortage of natural gas in Cook Inlet has severed that supply indefinitely.

Looking to diversify, GVEA announced last year that it had secured nearly $500 million in federal loans and grants that would help it vastly expand its use of renewables.

That money would pay for two battery systems to store power from new wind and solar projects when it’s not sunny or windy. It also would cover more than 60 miles of new transmission lines, allowing the utility to tap into proposed wind farms in the Interior.

But boosters of renewables have grown frustrated that the utility still lacks firm plans to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels. And now, the federal funds for GVEA’s infrastructure upgrades are in limbo amid the Trump administration’s broad freeze on green energy spending, according to Ashley Bradish, a spokesperson for the utility.

Federal officials on March 25 gave funding recipients a month to propose project changes that align with President Donald Trump’s executive order on “unleashing American energy” and to “remove far-left climate features.” GVEA was given only 500 characters to outline those revisions, utility officials said.

“Just within the last few weeks, GVEA’s job got a lot harder,” said Wight, the energy expert.

GVEA’s board voted in 2022 to shut down one of its two big coal power plants — a step toward lowering emissions and moving to renewables.

But the utility reversed course last year, citing the natural gas supply crunch and saying it would keep operating the coal plant until lower-cost alternatives became available.

Then, in August, it signed a new contract with Usibelli Coal Mine — the state’s only supplier of the fuel — to buy more feedstock for the plant, which burns some 200,000 tons of coal each year.

While coal comes with high carbon emissions, it’s relatively cheap, and utility leaders fear that replacing it with renewables could boost costs and reduce reliability for consumers.

If Golden Valley adds more wind and solar power, it would need a way to store energy and consistently distribute it, and “there’s a cost associated with that,” Bradish said. “Our current battery can’t provide that regulation.”

The utility has not released an analysis showing how rates would change if it were to replace fossil fuel-fired power with renewables.

“That’s part of what we’re studying,” Bradish said.

Some advocates, like Gagnon with Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition, say there’s also a cost associated with continuing to burn fossil fuels. GVEA is paying some $14 million to build two storage tanks at the Fairbanks-area oil refinery that it buys fuel from.

“The mines’ support of renewables is evidence for the cost-effectiveness of renewables,” said Gagnon. “Their bottom line is going to be cost.”

Kinross and Pogo — whose mines collectively account for about 30% of the utility’s energy sales — haven’t said how long they’ll wait on GVEA before building their own wind or solar farms.

Riedel, with Kinross, said her company wants to see GVEA take steps “soon,” but she would not elaborate.

“It is not our role to specify to GVEA as to its generation and power supply portfolio,” Riedel said. “What we need from our provider is electricity that is reliable, low cost and the least environmental impact possible. It is up to the provider to determine how to get there.”

GVEA communicates closely with Kinross and Northern Star about their emissions reduction targets, Bradish said.

Losing them as customers “absolutely would have an impact on our membership,” she added. “It’s something that is definitely thought about when we’re moving forward.”

Nathaniel Herz welcomes tips at natherz@gmail.com or (907) 793-0312. This article was originally published in Northern Journal, a newsletter from Herz. Subscribe at this link.