Discussion Of Use Of Subsistence Foods In Copper Valley: NPS

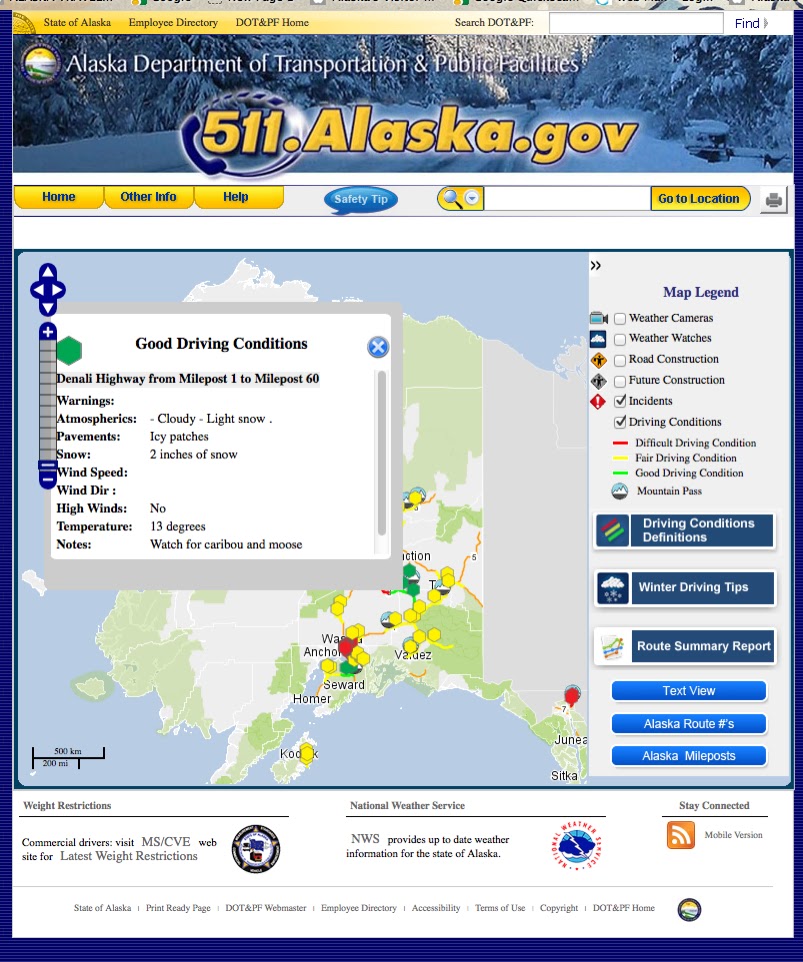

Copper River salmon in a smokehouse.Photo / Barbara Cellarius Community-led food security solutions in Alaska’s Copper River Valley Pre...

https://www.countryjournal2020.com/2024/11/discussion-of-use-of-subsistence-foods.html

|

| Copper River salmon in a smokehouse.Photo / Barbara Cellarius |

Press Release From National Park Service

By Laura Vachula, November 2024

Along the western edge of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, the cold, gray water of the Copper River flows 290 miles from the glaciated Wrangell Mountains to the Gulf of Alaska. The river, famous for its salmon runs, roars through forests, wetlands, and mountain valleys and past small communities—each with no more than a few hundred year-round residents.

The villages in the Copper River Valley are more than 190 miles from the shopping hubs of the Anchorage metropolitan area. A few small, independent stores provide grocery options. But serving such small communities, they have limited variety and can be very expensive.

Many people in the region meet or supplement their dietary needs by harvesting the wild foods that nature provides, like caribou, moose, berries, and salmon. Beyond the nutritional benefits, subsistence feeds the soul and is important in Alaska Native cultures. Wild foods are traditional foods, and subsistence activities are interwoven with cultural practices. Native and non-native residents in rural, park affiliated communities can participate in subsistence within and near Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, including fishing in the Copper River or hunting across the land. The park was established to protect the scenic beauty and wildlife in the area, as well as maintain opportunities for harvesting wild foods.

But climate change-related shifts in the environment are impacting the availability of wildfoods and conditions necessary to access them—such as rivers that don’t freeze in the winter like they used to and thus limit travel across the landscape.

“Subsistence resources are really important to the communities that have the ability to engage in subsistence harvest in Wrangell-St Elias, and we are hearing of challenges that our subsistence users are facing,” said Barbara Cellarius, cultural anthropologist and subsistence coordinator at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve.

With funding from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the National Park Service (NPS) is partnering with rural Alaskans on projects they’ve identified to mitigate the impacts of climate change on subsistence activities.

“In Alaska, people are part of the ecosystem,” said Mark Miller, ecologist at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve and project lead. “This funding will be awarded to partners for projects that enhance subsistence food security resilience in relation to climate change.”

The United Nations World Food Summit definition of food security is: “when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

Through a cooperative agreement with the NPS, the Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission (AITRC)—a local nonprofit based along the Copper River that represents the eight federally recognized Ahtna Tribes—is coordinating food preservation workshops and weekly in-season teleconferences, during which fishery managers and subsistence fishers can share the latest information about salmon runs and harvest with one another.

Subsistence in Alaska Native cultural traditions

People have hunted, fished, and gathered wild food in what is now Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve for thousands of years. Four Alaska Native groups—the Ahtna, Upper Tanana, Eyak and Tlingit—have ties to the area. Subsistence activities are essential to their cultures and traditional foods, feeding them physically and spiritually.

Working together, caring for others, and sharing the harvest are core values of subsistence. In many communities, villagers take turns operating a shared fish wheel—a structure placed in the river to catch fish—and bring salmon to elders.

Conservation is also intertwined with subsistence, as a necessity to sustain fish and wildlife populations and protect this way of life. When fishing, for instance, Ahtna traditionprescribes rules for treating salmon with respect and to maintain healthy populations over time. It is wrong to waste fish, and those who do will find it difficult to catch more.Now, despite those principles and practices—as well as a long history of advocating for theirrights to harvest wild foods—the resources are threatened by climate change and environmental uncertainties.Closed caribou hunting seasonThe Nelchina caribou herd can be found munching on moss, grasses, lichen, and flowers throughout the summer in the Talkeetna mountains—more than 100-miles west of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. They pass through the park in the spring and fall during their migration to their winter range near the Canadian border.

Caribou are well-adapted to the cold, dry conditions that characterize winter in many parts of Alaska, but climate change impacts are making survival more challenging. Increased precipitation and warmer temperatures have caused unusual winters with excessive snow, unseasonable rains, and cycles of freezing and thawing. Caribou use their large hooves to dig through snow to uncover lichen, their primary winter diet, but deep snow or layers of ice can make it nearly impossible for them to access food.

Caribou foraging for lichen under the snow. NPS Photo / Kyle Joly

Caribou foraging for lichen under the snow. NPS Photo / Kyle Joly

In recent years, Chinook (king) salmon have been returning to their Alaska spawning grounds in low numbers, regularly requiring fishing closures and restrictions. USFWS / Ryan HagertyEach year, fishers on the Copper River need to report how many fish they catch and which species, but the due date for reporting isn’t until the end of the season.

By hosting the calls weekly throughout the summer, AITRC hopes to bridge knowledge gaps, encourage communication, and build connections between fishery managers, scientists, nonprofits, subsistence fishers, and anyone else invested in the health of the river’s salmon.

“The teleconferences are an opportunity for state and federal agencies to hear from those upriver fishers without enforcing more reporting requirements,” Stanbro said.

During the calls, attendees from different communities along the river share anecdotes and information, beyond what’s requested in the end-of-season reports, such as fish sizes, water level fluctuations, and any diseases noticed. In return, they get to ask the fishery managers questions and voice any concerns.

“It’s nice to have a platform where people can feel a little more comfortable asking state and federal agencies questions,” Stanbro said.

Many families use a fish wheel to efficiently catch salmon. Submerged paddles are pushed by the river’s current, propelling it like a windmill, and the wheel’s large baskets scoop up fish swimming upriver. AITRC was inspired by the in-season teleconferences that were established for the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. The Yukon River teleconferences are hosted by the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association and have occurred regularly for nearly two decades. Beginning in 2024, the meetings are continuing with support from the Inflation Reduction Act.

As an ecologist, Stanbro is excited about what she and other scientists could learn from the Copper River teleconferences.

“Research-wise, we’re hearing about changes that are happening, and we could start documenting or analyzing that specific measurement,” she said.Future subsistence food security projectsThe food-preservation workshops and Copper River teleconferences coordinated by AITRC are just two examples of what will be accomplished with the Inflation Reduction Act funding.

As Cellarius has visited park-affiliated communities and met with Tribal councils, she’s heard many ideas about how to mitigate the impacts of climate change on harvesting wild foods. Future subsistence food security resilience projects might include building additional community fish wheels, producing elder-led programming for youth camps, or constructing a shared food-processing facility—a cool place to process game animals if outside temperatures are too warm.

“We want the funding to benefit a community of subsistence users. Not just a few individuals,” Cellarius said. The projects will be led by Tribal governments and local organizations, in partnership with the NPS.

Beyond supporting community-identified priorities, the NPS will use IRA funding to survey and monitor caribou, moose, and Copper River sockeye salmon in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. This will enable the park to update its population estimates and assess potential long-term impacts of climate change.

Along the western edge of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, the cold, gray water of the Copper River flows 290 miles from the glaciated Wrangell Mountains to the Gulf of Alaska. The river, famous for its salmon runs, roars through forests, wetlands, and mountain valleys and past small communities—each with no more than a few hundred year-round residents.

The villages in the Copper River Valley are more than 190 miles from the shopping hubs of the Anchorage metropolitan area. A few small, independent stores provide grocery options. But serving such small communities, they have limited variety and can be very expensive.

Many people in the region meet or supplement their dietary needs by harvesting the wild foods that nature provides, like caribou, moose, berries, and salmon. Beyond the nutritional benefits, subsistence feeds the soul and is important in Alaska Native cultures. Wild foods are traditional foods, and subsistence activities are interwoven with cultural practices. Native and non-native residents in rural, park affiliated communities can participate in subsistence within and near Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, including fishing in the Copper River or hunting across the land. The park was established to protect the scenic beauty and wildlife in the area, as well as maintain opportunities for harvesting wild foods.

But climate change-related shifts in the environment are impacting the availability of wildfoods and conditions necessary to access them—such as rivers that don’t freeze in the winter like they used to and thus limit travel across the landscape.

“Subsistence resources are really important to the communities that have the ability to engage in subsistence harvest in Wrangell-St Elias, and we are hearing of challenges that our subsistence users are facing,” said Barbara Cellarius, cultural anthropologist and subsistence coordinator at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve.

With funding from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the National Park Service (NPS) is partnering with rural Alaskans on projects they’ve identified to mitigate the impacts of climate change on subsistence activities.

“In Alaska, people are part of the ecosystem,” said Mark Miller, ecologist at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve and project lead. “This funding will be awarded to partners for projects that enhance subsistence food security resilience in relation to climate change.”

The United Nations World Food Summit definition of food security is: “when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

Through a cooperative agreement with the NPS, the Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission (AITRC)—a local nonprofit based along the Copper River that represents the eight federally recognized Ahtna Tribes—is coordinating food preservation workshops and weekly in-season teleconferences, during which fishery managers and subsistence fishers can share the latest information about salmon runs and harvest with one another.

Subsistence in Alaska Native cultural traditions

People have hunted, fished, and gathered wild food in what is now Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve for thousands of years. Four Alaska Native groups—the Ahtna, Upper Tanana, Eyak and Tlingit—have ties to the area. Subsistence activities are essential to their cultures and traditional foods, feeding them physically and spiritually.

Working together, caring for others, and sharing the harvest are core values of subsistence. In many communities, villagers take turns operating a shared fish wheel—a structure placed in the river to catch fish—and bring salmon to elders.

Conservation is also intertwined with subsistence, as a necessity to sustain fish and wildlife populations and protect this way of life. When fishing, for instance, Ahtna traditionprescribes rules for treating salmon with respect and to maintain healthy populations over time. It is wrong to waste fish, and those who do will find it difficult to catch more.Now, despite those principles and practices—as well as a long history of advocating for theirrights to harvest wild foods—the resources are threatened by climate change and environmental uncertainties.Closed caribou hunting seasonThe Nelchina caribou herd can be found munching on moss, grasses, lichen, and flowers throughout the summer in the Talkeetna mountains—more than 100-miles west of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. They pass through the park in the spring and fall during their migration to their winter range near the Canadian border.

Caribou are well-adapted to the cold, dry conditions that characterize winter in many parts of Alaska, but climate change impacts are making survival more challenging. Increased precipitation and warmer temperatures have caused unusual winters with excessive snow, unseasonable rains, and cycles of freezing and thawing. Caribou use their large hooves to dig through snow to uncover lichen, their primary winter diet, but deep snow or layers of ice can make it nearly impossible for them to access food.

Many people rely on caribou, but the Nelchina herd’s population has dropped dramatically—from a minimum of 53,000 caribou in 2019 to 6,983 caribou in 2023. In 2024, the herd’s range was closed to caribou hunting for the second year in a row. Based on past data, wildlife managers predict that it may take 15 years or more for the population to recover.

As climate change shifts the ecosystem, people may need to become more dependent on salmon—a fish that could face its own climate-related struggles, such as warmerwater temperatures causing heat stress and reducing habitat.

Through the Inflation Reduction Act funding, Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission is leading two food security projects for the communities affiliated with Wrangell-St. Elias—focused on efficient harvest and use of fish, as well as protecting salmon runs.Nourished by salmon year-roundFrom toilet paper to baby formula, stress from supply chain uncertainty was felt nationwide during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was perhaps even more intense in rural areas of Alaska, including in the Copper River Valley, as transportation bringing food from out of state was disrupted.

It was a reminder of the value of subsistence and the benefit of not relying on the outside world to keep pantries and freezers stocked.

“COVID-19 affected many communities and made us realize that it’s really important to be able to preserve food from summer to winter,” said Kelsey Stanbro, ecologist at AITRC.

Collaborating with the NPS, one of AITRC’s IRA-funded projects will create opportunities for people to learn different methods for preserving salmon, such as canning or smoking. AITRC will host two food-processing and preservation workshops annually, beginning in 2025.

If properly prepared, canned salmon is shelf-stable for several years. NPS Photo / Barbara Cellarius“If you’re new or haven’t learned from someone else, this will be an opportunity to learn to process and preserve these really important subsistence resources in this region,” Cellarius said.

Stanbro and her team will seek out people who are interested in sharing their recipes.

“We’re hoping to bring in some knowledge-holders who can teach the methods that are traditionally used or are being lost,” she said.

The workshops will be open to all interested community members, and the AITRC team is especially excited to engage Tribal citizens and youth.

“Passing it down is important to keep some of these traditions alive,” Stanbro said. She hopes that participants will use the preservation methods at home and introduce the techniques to relatives and friends.

“I think the workshops could spark a wider amount of food processing and preservation, just by teaching a couple people,” she said. On a Thursday at 11 a.m., names pop onto screen, as a virtual meeting begins.

After introductions and listing ground rules—be respectful, wait your turn, state your name and where you fish—each attendee has a chance to speak.

A fishery manager from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game reports the number of sockeye salmon detected by sonar and delivers news about a decision to end the Chinook salmon fishing season early because of low numbers of the species.

A researcher asks the group to keep an eye out for salmon with radio tags and reminds them how to return any tags they catch so that data about the fate of the tagged fish can be retrieved and analyzed.

One subsistence fisher voices concerns about the Chinook (king) salmon fishing closure.

Another subsistence fisher near Chistochina reports that she hasn’t caught many fish, and village residents are worried about feeding their families.

From downriver, a subsistence fisher confirms that fishing has also been slow for her community, and she’s noticed many salmon are smaller than usual.

Once everyone has spoken, the meeting ends. They’ll come together again the following week.

The meetings might seem basic, but they’re accomplishing something that hasn’t existed before: an outlet for sharing timely observations and information among fisheries managers and upriver subsistence fishers during the Copper River fishing season.

As climate change shifts the ecosystem, people may need to become more dependent on salmon—a fish that could face its own climate-related struggles, such as warmerwater temperatures causing heat stress and reducing habitat.

Through the Inflation Reduction Act funding, Ahtna Intertribal Resource Commission is leading two food security projects for the communities affiliated with Wrangell-St. Elias—focused on efficient harvest and use of fish, as well as protecting salmon runs.Nourished by salmon year-roundFrom toilet paper to baby formula, stress from supply chain uncertainty was felt nationwide during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was perhaps even more intense in rural areas of Alaska, including in the Copper River Valley, as transportation bringing food from out of state was disrupted.

It was a reminder of the value of subsistence and the benefit of not relying on the outside world to keep pantries and freezers stocked.

“COVID-19 affected many communities and made us realize that it’s really important to be able to preserve food from summer to winter,” said Kelsey Stanbro, ecologist at AITRC.

Collaborating with the NPS, one of AITRC’s IRA-funded projects will create opportunities for people to learn different methods for preserving salmon, such as canning or smoking. AITRC will host two food-processing and preservation workshops annually, beginning in 2025.

If properly prepared, canned salmon is shelf-stable for several years. NPS Photo / Barbara Cellarius“If you’re new or haven’t learned from someone else, this will be an opportunity to learn to process and preserve these really important subsistence resources in this region,” Cellarius said.

Stanbro and her team will seek out people who are interested in sharing their recipes.

“We’re hoping to bring in some knowledge-holders who can teach the methods that are traditionally used or are being lost,” she said.

The workshops will be open to all interested community members, and the AITRC team is especially excited to engage Tribal citizens and youth.

“Passing it down is important to keep some of these traditions alive,” Stanbro said. She hopes that participants will use the preservation methods at home and introduce the techniques to relatives and friends.

“I think the workshops could spark a wider amount of food processing and preservation, just by teaching a couple people,” she said. On a Thursday at 11 a.m., names pop onto screen, as a virtual meeting begins.

After introductions and listing ground rules—be respectful, wait your turn, state your name and where you fish—each attendee has a chance to speak.

A fishery manager from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game reports the number of sockeye salmon detected by sonar and delivers news about a decision to end the Chinook salmon fishing season early because of low numbers of the species.

A researcher asks the group to keep an eye out for salmon with radio tags and reminds them how to return any tags they catch so that data about the fate of the tagged fish can be retrieved and analyzed.

One subsistence fisher voices concerns about the Chinook (king) salmon fishing closure.

Another subsistence fisher near Chistochina reports that she hasn’t caught many fish, and village residents are worried about feeding their families.

From downriver, a subsistence fisher confirms that fishing has also been slow for her community, and she’s noticed many salmon are smaller than usual.

Once everyone has spoken, the meeting ends. They’ll come together again the following week.

The meetings might seem basic, but they’re accomplishing something that hasn’t existed before: an outlet for sharing timely observations and information among fisheries managers and upriver subsistence fishers during the Copper River fishing season.

In recent years, Chinook (king) salmon have been returning to their Alaska spawning grounds in low numbers, regularly requiring fishing closures and restrictions. USFWS / Ryan HagertyEach year, fishers on the Copper River need to report how many fish they catch and which species, but the due date for reporting isn’t until the end of the season.

By hosting the calls weekly throughout the summer, AITRC hopes to bridge knowledge gaps, encourage communication, and build connections between fishery managers, scientists, nonprofits, subsistence fishers, and anyone else invested in the health of the river’s salmon.

“The teleconferences are an opportunity for state and federal agencies to hear from those upriver fishers without enforcing more reporting requirements,” Stanbro said.

During the calls, attendees from different communities along the river share anecdotes and information, beyond what’s requested in the end-of-season reports, such as fish sizes, water level fluctuations, and any diseases noticed. In return, they get to ask the fishery managers questions and voice any concerns.

“It’s nice to have a platform where people can feel a little more comfortable asking state and federal agencies questions,” Stanbro said.

Many families use a fish wheel to efficiently catch salmon. Submerged paddles are pushed by the river’s current, propelling it like a windmill, and the wheel’s large baskets scoop up fish swimming upriver. AITRC was inspired by the in-season teleconferences that were established for the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. The Yukon River teleconferences are hosted by the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association and have occurred regularly for nearly two decades. Beginning in 2024, the meetings are continuing with support from the Inflation Reduction Act.

As an ecologist, Stanbro is excited about what she and other scientists could learn from the Copper River teleconferences.

“Research-wise, we’re hearing about changes that are happening, and we could start documenting or analyzing that specific measurement,” she said.Future subsistence food security projectsThe food-preservation workshops and Copper River teleconferences coordinated by AITRC are just two examples of what will be accomplished with the Inflation Reduction Act funding.

As Cellarius has visited park-affiliated communities and met with Tribal councils, she’s heard many ideas about how to mitigate the impacts of climate change on harvesting wild foods. Future subsistence food security resilience projects might include building additional community fish wheels, producing elder-led programming for youth camps, or constructing a shared food-processing facility—a cool place to process game animals if outside temperatures are too warm.

“We want the funding to benefit a community of subsistence users. Not just a few individuals,” Cellarius said. The projects will be led by Tribal governments and local organizations, in partnership with the NPS.

Beyond supporting community-identified priorities, the NPS will use IRA funding to survey and monitor caribou, moose, and Copper River sockeye salmon in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. This will enable the park to update its population estimates and assess potential long-term impacts of climate change.