$11 Milk In Rural Alaska. Planting Traditional "Indian Potatoes".

Amid Ongoing Threats To Local Food Systems, Alaska Native & Rural Alaskan Leaders Imagine Alternatives Lettuce (Photo, Country Journal)...

Amid Ongoing Threats To Local Food Systems, Alaska Native & Rural Alaskan Leaders Imagine Alternatives

Investing in the Soil

In running the Metlakatla Indian Community S’ndooyntgm Galts’ap Community Garden, Gatgyeda Haayk has developed a particular relationship to soil. “People misunderstand soil,” she explained.

Alongside permafrost, extreme climate, and a short growing season, poor soil is often cited as a reason why gardens will not grow in Alaska. “A lot of people think you could just throw something in the ground where it’s not that easy because our soil is so acidic,” Haayk said.

However, Haayk’s garden thrives. Watermelons and pumpkins, green onions, beets, potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers, peas, beans, corn – Haayk grows a mix of Southeast Alaska staples and new plants.

The key is the dirt – investing in healthy soil can be a decades-long process. “The time and the effort and the love and all the energy – the soil that I have now, I built that soil,” Haayk said.

The investment is worth it to Haayk, because she believes community gardens help solve a basic challenge facing rural Alaskans: putting food on the table.

Alaska’s rural retail grocery system is extremely costly to maintain, leading to unparalleled logistics challenges and famously expensive cheese. This is one reason the main source of food in rural Alaska is subsistence and personal use gathering. However, climate change, state and federal policy, and commercialization have disrupted longstanding practices of living off the land.

As both retail and non-retail food systems come under stress, rural Alaskans are all the more willing to try new (and old) ways of obtaining food that align with their values, their budgets and their tastes.

Small Planes and Fragile Supply Chains

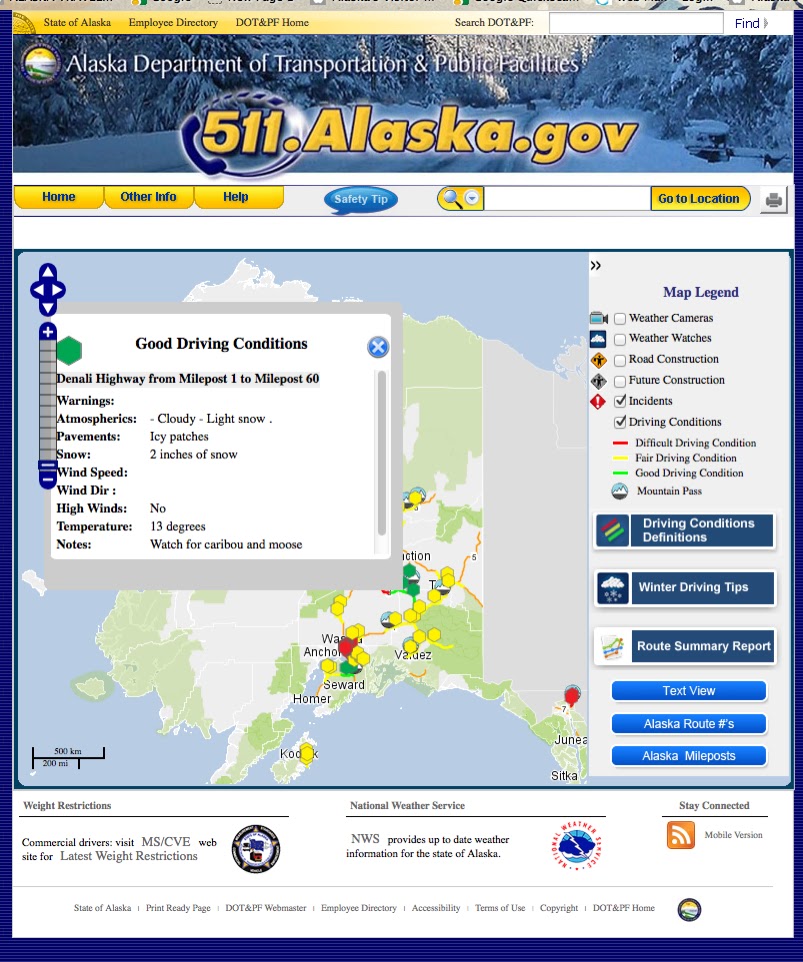

More than 80% of Alaska communities are not connected to a central road network year round. These towns and villages are spread out over a tract of land two and a half times the size of Texas at the absolute periphery of the United States. Maintaining grocery stores is often impossible.

Additionally, Alaska is largely dependent on food from out of state. Mike Jones, an economist who studies rural food systems at the University of Alaska Anchorage, told the Daily Yonder in an interview that the food supply chain to remote Alaska is perhaps the most complex in the nation.

Imported food reaches Alaska by plane or, mostly, by boat to the Port of Alaska. From there in-state suppliers rely on a “hub and spokes model” to get the food out to regional depots where it is then shuttled on to individual communities. “It is not so much planes, trains and automobiles as it is planes, barges and snowmobiles,” Jones said.

Each link in the supply chain raises costs for the end consumer and raises the likelihood of something going wrong in transit.

Outages ground planes and forsake food to hangars that usually lack sufficient cold storage capacity. In September of 2024, there were 55 unscheduled outages. That means a lot of rotting food. “Combine this with other issues like runway plowing, maintenance, labor constraints … you get major backlogs” Jones said. This jacks up the price of produce in rural Alaska, where average household income in some areas is as low as $36,753.

“That’s how you end up paying $11 for a gallon of milk,” said Bruce Botelho, former Attorney General of Alaska who was part of the effort to oppose the recent Kroger Albertsons merger. “Rural Alaska is a tiny market spread across vast geography … it is very difficult to establish competitive prices and availability,” Botelho told the Daily Yonder.

Traditional Foodways

Eva Burk is Dena’ Athabascan. Growing up, her family lived on a fish camp on the Tanana River about 50 miles south of Fairbanks. Large portions of her diet and her family’s livelihood came from the trapline. “My dad was born before Alaska had statehood… He was born a free man, him and his family could choose when and where and how much to fish and hunt and trap,” Burk said.

Burk was born 10 years after the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) passed in Congress, a time when Alaska Native people were still “getting adjusted to capitalism … adjusting to owning land and getting engaged in the cash economy,” Burk said. ANCSA, and subsequent state and federal action, brought huge disruptions to day-to-day life for many Alaska Native people.

Burk has spent her career tracing the ongoing effects of these changes on Alaska Native food systems. Burk studies rural community development at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and serves on advisory panels for the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, The Federal Subsistence Board, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

A 2004 report found that subsistence accounted for 29-69% of caloric intake in off-road communities. Personal use gathering and hunting has become more expensive as inflation drives up supply costs (like fuel and equipment) and regulation drives up permit costs. Climate change and commercial overuse have jeopardized key subsistence resources. Fisheries that have sustained Alaska native communities for millennia are in crisis.

“We’ve been shut down from subsistence fishing for five years now,” said Burk, explaining that salmon depopulation sets off a series of cascading consequences for the subsistence system. Less salmon means increased predation of caribou calves and moose, both species traditionally vital to subsistence lifestyles. Loss of access to land and subsistence resources has forced Alaska Native communities to alter the food they eat. A University of Alaska Fairbanks report cites growing consumption of processed foods as a reason for higher instances of diabetes, childhood dental cavities, and colorectal cancer.

Perhaps the most insidious threat is cultural loss. Burk worries that the next generation won’t have access to the methods of fishing, trapping, and hunting that her people have prized as part of a fundamental connection to nature. “Everything is spiraling out of control,” Burk said.

Continuing a History of Adaptation

The challenges are steep, but Gatgyeda Haayk noted that for the thousands of years people have lived in Alaska, they have overcome intense obstacles to forage, gather, and hunt food in some of the world’s most extreme environments. That history is not stagnant, but adaptive. Haayk said that when Tsimshian people migrated to New Metlakatla from British Columbia, they brought plants of value to them and helped them grow in their new environment. “Even though we aren’t, what they say, “traditional farmers,” we have also had our ways of cultivating the land,” Haayk said.

According to Burk, the work to adapt and maintain Alaska Native food sovereignty for 2025 and beyond happens at three levels: systems, community, and individual.

Much of Burk’s focus is on systems change. Her “four buckets” of work are “water stewardship, food sovereignty, cultural revitalization, and community wellness.” This means that one day she is in a North Pacific Fishery Advisory Panel meeting, trying to reduce bycatch (the incidental catch of unintended species) and the next day she is working to secure financing for a community buy-back project to build a small farm in Nenana. “Many of us have to wear a lot of hats in this work … but that’s what it takes to have Indigenous voices represented in the decision-making spaces,” she said.

At the community level, Heidi Rader, Director of the Alaska Tribes Extension program out of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, works to teach practices that enhance rural food security and Alaska Native food sovereignty. Spreading knowledge means meeting people; via an Alaska gardening blog, youtube videos about stewarding wild blueberries, or workshops on how to can salmon.

Finally, Gatgyeda Haayk helps individuals adopt the practice of gardening. Because gardening is not widespread in rural Alaska, getting started can be daunting. Locals may not know what grows in their area. Haayk has tried to create a space where gardeners can learn from each other. Experimentation has led to new discoveries, like how to grow healthy pumpkins in a short season. It has also led to the recovery of lost growing practices.

Cultivating “Indian potatoes” in Metlakatla was once widespread, but Haayk was only able to find one family still growing them. That family gifted Haayk six potato starters. “Two years ago, I was able to grow over 100 pounds of potatoes,” Haayk said. She gave half of her harvest to the elders. “For them to have that connection to a piece of our heritage that was kind of lost. And then to see more and more community members want to grow that potato and be connected to it. It’s eating a part of our history.”

Economic analysts sometimes doubt whether these sorts of solutions can scale to a level that fills the massive gaps of Alaska’s rural food system. However, to many food security advocates, solutions that only consider how to produce the cheapest calories miss the point.

“I lost my daughter in 2006, I had always wanted to do a healing garden for her,” Haayk said. Haayk had spent years building up the community garden in Metlakatla in her daughter’s memory, when Covid-19 hit. The pandemic threatened to cut off the one food supply barge Metlakatla, an island community, relies on for basic goods and produce. Haayk’s garden became a community resource and people who had never gardened before started planting in her plots.

Food intertwines economic, cultural, health, spiritual values. That means when a food-system suffers, it can have deep, corrosive effects. To combat this, Burk emphasizes leaning on cultural strengths. “Sharing in the bounty and having potlatch [an Indigenous gift-giving feast], which is our culture. That’s how we get by and survive,” Burk said.