America's Seafood Processing Industry Needs International Workers To Succeed, Say America's "Coastal Senators"

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON Alaska Sen. Murkowski and other US lawmakers seek guest worker visa exception for seafood industry The legislation ...

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON

Alaska Sen. Murkowski and other US lawmakers seek guest worker visa exception for seafood industry

The legislation would exempt seafood companies from a cap on the number of international workers they can hire through the temporary H-2B visa program

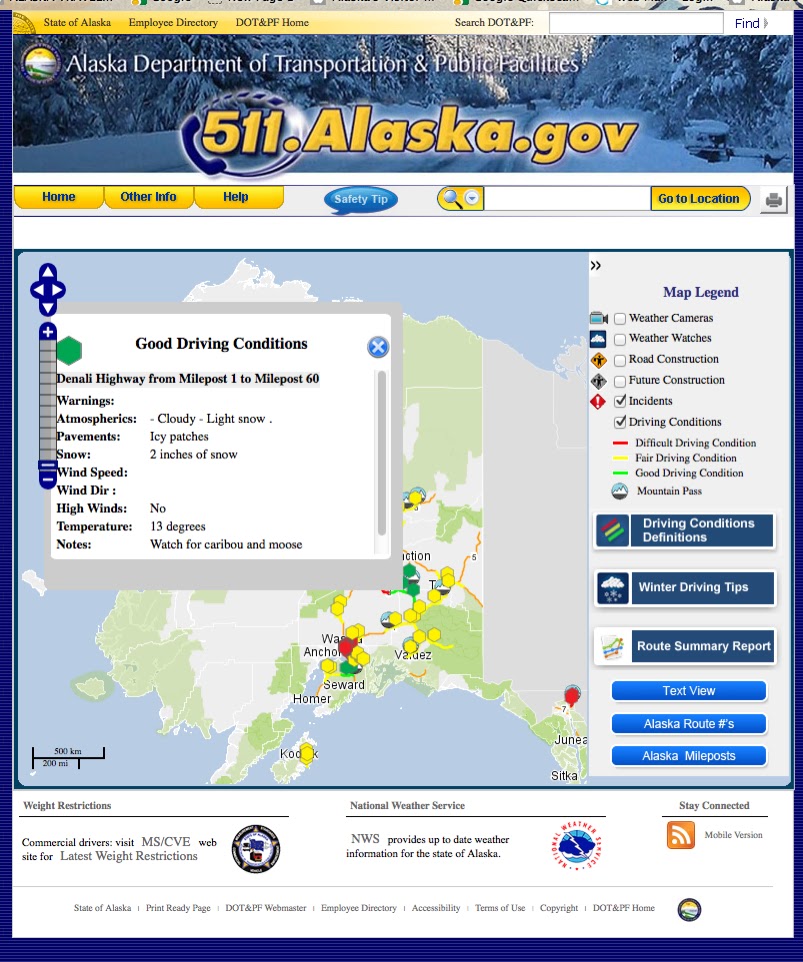

Alaska U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski and other coastal senators have proposed new legislation to exempt seafood processing companies from a cap on the number of international workers they can hire through the temporary H-2B visa program.

The Alaska seafood industry regularly recruits and hires workers from around the world each year, including Mexico, the Philippines and Ukraine. Companies must demonstrate they are unable to fill processing jobs with American workers, and then through the temporary H-2B visa program, they hire thousands of guest workers to meet the needs of Alaska’s labor-intensive, high-volume commercial fishing seasons.

Seafood processing companies must apply each year for a number of H-2B visas in order to hire workers, competing with various nonagricultural sectors, including construction, landscaping and hospitality industries. Currently, Congress has set the cap at 66,000 visas per year, split evenly between the time periods of October through March and April through September.

Under the proposed legislation, the Save Our Seafood Act, seafood companies would be exempt from caps on these visas, to allow hiring of international workers as needed.

“Alaska’s seafood industry is a delicate chain — and when processors don’t have the workforce to meet demand, the whole industry can fall apart,” Murkowski, R-Alaska, said in a written statement announcing the legislation.

“Coastal communities, family-owned fishing boats, and Alaskans who work in the industry need to know that they have fully-functioning operations where they can deliver their catch,” she said. “Through this legislation, I’m working to ensure that the industry has a dependable workforce that can process and deliver the highest-quality seafood in the world.”

Murkowski introduced similar legislation in 2023, but it failed to advance in Congress. Several U.S. senators from Virginia, Maryland and Louisiana signed on as co-sponsors of the legislation to support their fishing industries, including crab and shrimp fleets.

No other industry in Alaska relies as heavily on out-of-state workers as seafood processing, which increased to over 80% nonresident workers in 2023, according to an analysis by the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development. The number of Alaska seafood processor jobs has also declined over the last decade, and totaled 8,495 in 2023, the most recently available number.

Alaska’s seafood industry has also taken a hit in recent years, with a “perfect storm” of declining fish prices, global market competition, and rising costs to bring products to market.

But despite Alaska’s seafood market woes, the labor needs of the processing industry remain the same, said Brian Gannon, vice president of government relations at LaborMex, a Texas-based company that connects employers with international workers through the H2 visa program.

“You still need a lot of people to touch individual fish to feed the machines,” he said.

Seafood processing workers handle fish unloaded from commercial fishing vessels, from sorting, cleaning and cutting, to freezing, canning and packaging. Though processing plants have become more efficient, Gannon noted Alaska seafood processing has always relied on out-of-state labor.

“It’s consistent with the last 100 years, that hasn’t changed,” he said. “Because in the remote coastal communities there is no workforce that is available, that is ready and not already engaged in the fishing or tendering effort. There’s just a severe lack of human capital in those regions.”

In 2023, Alaska employers applied for 825 guest workers via the H-2B visa program, according to the Alaska Department of Labor, and 554 were for seafood processor roles. Visas are valid for up to three years, and there were an estimated 1,500 international workers each year, Gannon has said.

Gannon estimates the workforce needed for Alaska is more like 4,000 jobs for the peak summer fishing seasons. “The industry needs to fight for a place within the 66,000 annual visas,” he said. “And the seafood industry needs to compete with landscapers, hotel operations, amusement parks, horse racing stables, grass cutters, lawn mowers, to provide workers or to have access to workers to cut fish.”

Gannon said the proposed legislation to exempt the seafood industry from the visa cap would benefit businesses. “Those employers would not have to worry about, ‘Are we going to have access to visas this year or not?’” he said. “It would be obviously very helpful for the Alaska seafood industry, and the U.S. seafood industry.”

Each year, seafood companies host job fairs abroad, and contract companies such as Gannon’s to assist with recruiting and hiring. Workers go through a hiring process, background check and visa interview, then if they are approved, seafood companies arrange their travel and airfare to work in Alaska’s over 70 onshore plants and 15 at-sea catcher-processor vessels.

Gannon argued the cap does not reflect the current need for guest workers in nonagricultural industries nationwide. “There’s only so many visas allowed by the federal government for workers to come in, and that’s an arbitrary number that was set 20 or 25 years ago. It’s only in the last six years that that cap has been hit, where the employers are requesting more visas than than are available, and now it’s up to a factor of three or four times,” he said. “I believe most likely that that number should be 200,000 or 300,000 visas to reflect the needs of industry.”

The Trump administration’s escalating crackdown on immigrants and ramped up deportations could present a dilemma for U.S. industries that rely on immigrant labor.

Ganon said while there is worry and concern, there is a precedent for the Trump administration prioritizing food industries. “When COVID hit, the administration quickly allowed for workers from Mexico and other countries that were in jobs and having nexus to food security, and U.S. food production, and they came in,” he said. “So we believe that the literal actions surrounding visas and critical food jobs, or food producing jobs, will remain an actual priority of this administration, regardless of words that come out of Washington, D.C.”

Gannon noted that interest is still high among international workers, as wages are $16.50 per hour for processing jobs this year, with airfare, housing and meals included and promised overtime.

If the bill is passed in Congress, it would be enacted for next year’s fishing season, in 2026. In the meantime, Gannon says industry advocates hope to garner support for the guest worker program, and the seafood industry. “There’s so many challenges, and but for a few administrative strokes by the federal government, they could do their part to really help employers in Alaska, and this would be a big thing to safeguard the industry,” he said.