End of An Era: "Magic Bus" Airlifted Off The Stampede Trail After Locals Get Tired Of It All

McCandless' Bus Ends Up At University of Alaska Museum At the end of the summer of 1992, some moose hunters near Denali National Park ...

McCandless' Bus Ends Up At University of Alaska Museum

At the end of the summer of 1992, some moose hunters near Denali National Park were on the old Stampede Trail, by the coal mining town of Healy. That's when they came across the body of a man, lying dead inside a rusty, ancient abandoned bus. Healy is at Mile 251 on the Parks Highway, 40 miles north of Cantwell – right where the historic linguistic boundaries of the Ahtna region blend into the Tanana.

|

| A tourist recreates "Alexander Supertramp's" iconic pose at the actual bus on the Stampede Trail in May, 2007. (Photo by RJ Patel, given to Copper River Country Journal) |

There are two major players in this story: a young man and a bus.

The man was Chris McCandless. The bus was a rusty, multi-colored Fairbanks city bus, which had, years before, been hauled out onto a 1903 lignite mining trail to serve as temporary housing for workers. The 1940's era bus was used by the Yutan Construction Company to build a wilderness access road. It was an early-day makeshift mobile home, roughly fitted with a bed and a wood barrel stove. Left for years to rust in the bushes, the bus was appropriated by McCandless, an urban drifter looking for something he thought he'd found. This was where he played out his last days, adopting a new fictional persona for himself – "Alexander Supertramp." And it was where he proceeded to starve to death.

NOT AN UNUSUAL STORY

The story of Chris McCandless was not remarkable. Over the years, many people have gone missing in Alaska. Many have been found dead, or never found at all. What was new about this tale was the eventual, unlikely celebration and exaltation of McCandless' series of avoidable errors. Mistakes that many rural Alaskans believe were unnecessary.

When hit author Jon Krakauer wrote the story about McCandless' death, in a book called "Into The Wild," it became an instant best seller. McCandless was elevated to near-sainthood by millions of readers around the world. Even "The Bus" (or what incongruously became known as "The Magic Bus" in spite of its ratty appearance) took on a mystical aura.

CANTWELL CONNECTION

In 2006, the actor Sean Penn arrived in Alaska at Cantwell, determined to make the book into a movie about the young man's life.

The film crew hired Alaskan locals living near Healy to go back into the old bus on the Stampede Trail on their snowmachines to scope it out. True to reality, though, the bus was not in a safe place. It was dangerous out there.

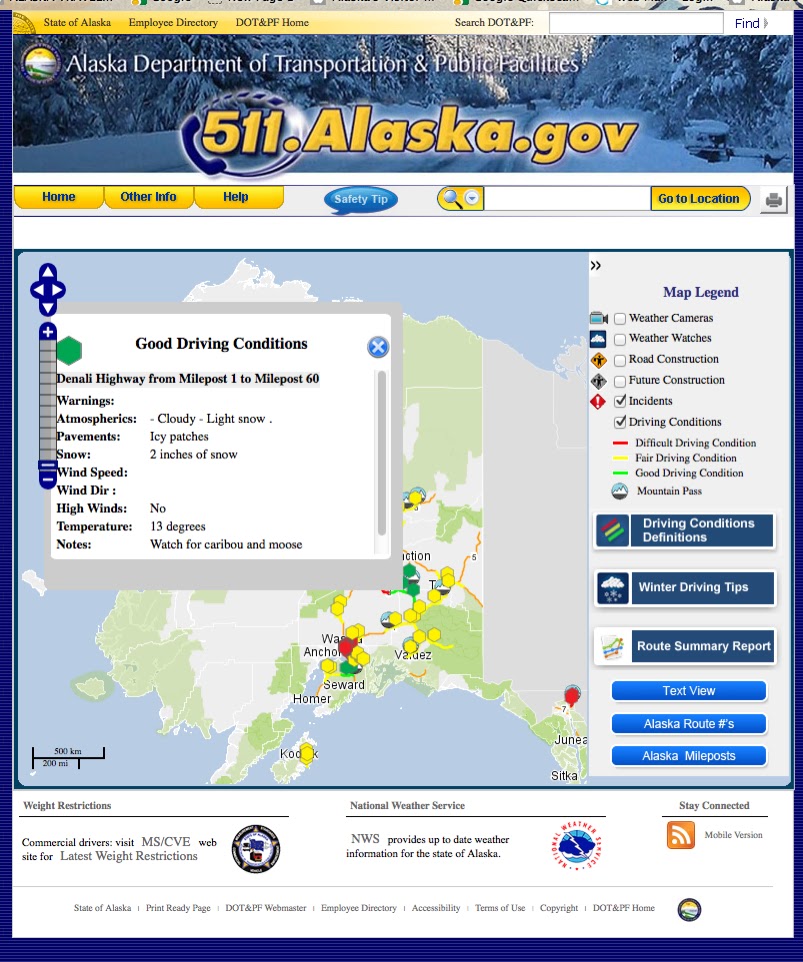

So Paramount found a place to film its movie that was more convenient. This spot was in Ahtna Country, not far from Cantwell, off the Denali Highway entrance on the Parks. The movie location was a place you could get to by car, where you didn't have to ford a dangerous river. And also, it had the added bonus of a distant view of Mt. McKinley (which the actual location did not have.)

That was handy. Paramount wanted to take a photo of the actor who played McCandless for the movie promotion. It would look great, him sitting on top of his bus, the mountain in full view behind him.

The movie company, though, couldn't do the film without the bus. So they found another one, which they rigged up as a stunt double: an exact replica of Fairbanks Bus #142 – down to the peeling paint.

STUNT DOUBLE BUS IN HEALY

After the film was done, the stunt double bus kicked around Cantwell for awhile. Eventually, it made its way to 49th State Brewing in Healy, where it became an attraction. People going to 49th State for a drink or two could walk around in the Hollywood version of the bus, looking at the replica bunk where Alexander Supertramp's dessicated body was found.

And they could take photos of themselves outside the stunt bus on metal folding chairs – just like the iconic photo that McCandless took of himself in front of the real bus and that was in Krakauer's book.

|

| The duplicate "stunt double" bus that was used in the film – at 49th State Brewing in Healy. (File Photo, Copper River Country Journal) |

HAPLESS PILGRIMS

Meanwhile, there was an increasing interest in taking a pilgrimage out the long and muddy Stampede Trail to the actual site of the bus where McCandless died. In spite of endless warnings from the National Park Service and others that this was dangerous and that river crossings were harrowing, groupies continued going out there. The trail became trampled. There were tips on the internet of how to get across the river.

There were guidebooks, too, that encouraged people to go out to the bus. The web went so far as to present The Magic Bus as if it were a hotel.

On the web, people wrote suggestions on how to make the experience of visiting the bus more comfortable.

GOOGLE REVIEWS OF THE MAGIC BUS:

"They should put a refrigerator (there) so you can store your meats."

"No toilet...or wifi but that was fine. I would stay there again."

"Not the best bed in the world."

Naturally, visiting the bus didn't always go

that well. In the course of trying to duplicate McCandless' adventure,

two women died. One was from Switzerland. She died in 2010. The other

was from Belarus, and she drowned in 2019. Just in the past 10 years, 15

major search-and-rescues involving the Magic Bus, including one with 5

Italian winter tourists, have taken place.

BACK HOME IN FAIRBANKS

In June, 2020, the Alaska Army National Guard airlifted the bus by helicopter out of the wilderness. For several months – as if the bus were a vice president, hidden away during a major world crisis – Bus #142 was sequestered in "a secure unknown location."

Moving the bus made international news. But it was something that people in the Healy area and along the Denali Corridor had been recommending for years. Because after all, they were the ones that had to go out and save people who got into trouble.

In September, 2020, the actual bus arrived, with huge fanfare, at the University of Alaska Museum in Fairbanks, where it will get a new home and be "restored" as a piece of Alaskan history.

Saturday, September 26, 2020. Copper River Country Journal