What If That Styrofoam & Plastic Bubble Wrap Could Be Replaced – Thanks To Alaska?

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON https://alaskabeacon.com/ Fungi and spruce may help solve Alaska’s plastic pollution problem All-natural Alaska mat...

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON

https://alaskabeacon.com/

Fungi and spruce may help solve Alaska’s plastic pollution problem

All-natural Alaska materials are being tested as a replacement for plastic foam, a ubiquitous product with a big carbon footprint and big impacts on ecosystems

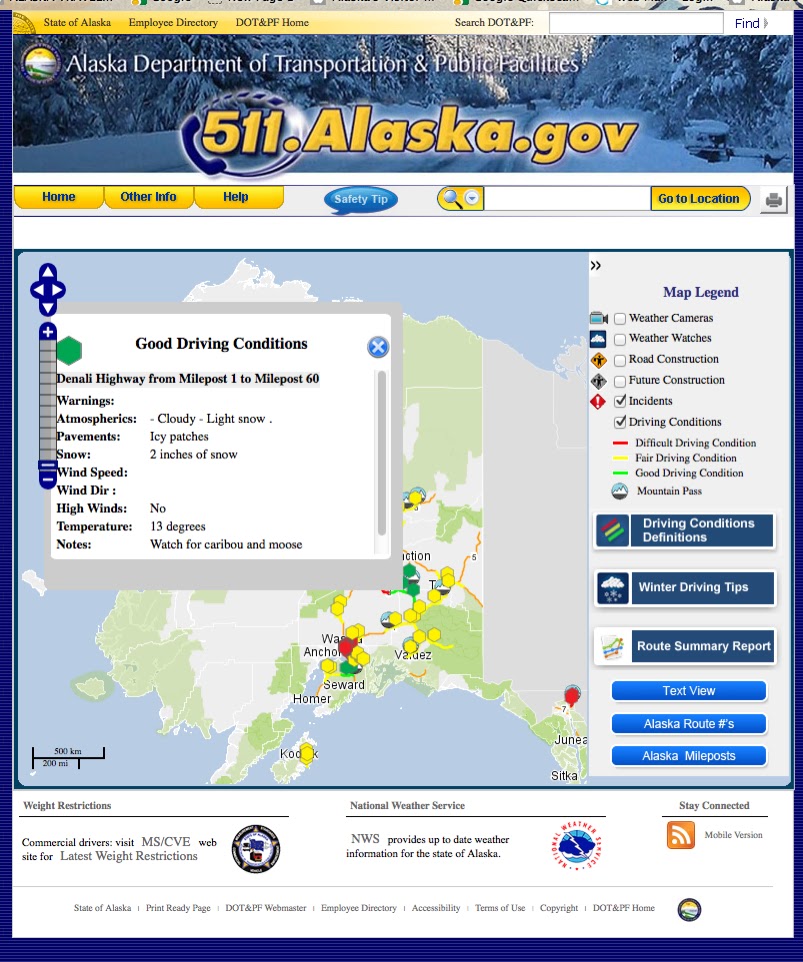

Nick Beckage, a graduate researcher, Davin Louangaphay, a research assistant, and Philippe Amstislavski, a professor of health sciences, stand among spruce trees on the University of Alaska Anchorage campus on April 30, 2025, with one of the insulating seafood boxes they created with a cellulose-mycelium blend. (Photo by Yereth Rosen/Alaska Beacon)

Every year, copious amounts of plastic foam boxes are used to ship Alaska seafood.

Instead of using plastics that contribute huge amounts of carbon emissions in their manufacture and huge amounts to pollution after their disposal, could Alaskans use environmentally friendly local materials to ship fish and provide other insulation?

Philippe Amstislavski, a professor of public health at UAA, and his colleagues have created an insulation box from a blend of cellulose and fibers from fungi. To him, it is an appropriate invention for Alaska, where he estimates that more than 1 million plastic foam boxes are used annually to hold fish.

“Our economy is dependent on seafood. And the ability to get fish to markets is really important,” he said. But while Alaskans value sustainable fish harvests, what about sustainable fish shipments? “How do we become materially independent?” he asks.

One solution, he believes, lies in materials that exist in abundance in Alaska’s boreal forest, including the woods on and near UAA’s campus: dead trees and fungi.

The key ingredient is mycelium, the fibrous, vegetative part of fungi. Mycelium creates a strong bond when it is weaved into web-like structures. Amstislavski and his team grow mycelium in their lab in cellulose foam created from wood pulp. The resulting material that, when dried, is durable, insulating and water-repellent. The growth process takes just days.

The work addresses a global problem with special Alaska significance.

Over its lifetime, Styrofoam and similar plastic insulating foam are carbon intensive.

The product itself is generally made from fossil fuels. Its manufacture uses the energy from more fossil fuels. Though lightweight, it must be transported over long distances to reach Alaska, which also requires fossil fuels. As it ages, plastic foam can release gases known as volatile organic compounds. When it breaks down into debris, the foam crumbles into increasingly small pieces, eventually becoming tiny microplastics swirling in the ecosystem that are difficult to see and nearly impossible to corral but create a big impact.

“It’s this whole, kind of perfect cycle of carbon emissions and pollution that they’re generating every time you use it,” Amstislavski said. “So how do you break it up? How do you challenge it? How do you create alternatives?”

Plastic impacts on Alaska

For marine- and fish-dependent Alaska, where disposal or recycling options are limited, plastic pollution is a serious problem, even in remote locations.

Microplastics from distant sources have become concentrated in high latitudes, brought north by ocean and atmospheric currents.

Climate change, which is amplified in the far north, has helped concentrate microplastics in the region because debris previously locked into sea ice or glacier ice is now being released through accelerated melt.

A study by Chinese researchers published earlier this year found microplastics in every single ice sample taken from Elson Lagoon in Utqiagvik, the nation’s northernmost community, and from every sample of Chukchi Sea ice taken nearby off the coast of Point Barrow, the spit of land extending north from town. An earlier study found microplastics in every sample taken from waterways in Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, and in other waterways in Southcentral Alaska.

Microplastics have been found in the bodies of walruses harvested by Indigenous hunters in the Bering Strait region, in fetuses of spotted seals and in Alaska fish such as pollock.

“I was driving to Eagle River, and I was looking at the side of the highway, and there was a bunch of plastic trash laying on the side,” said Davin Louangaphay, one of the technicians. “And I was, like, ‘Wow, there’s so much out there.’ And I feel like it’s just been increasing over the years as I’ve grown up.”

Eco-friendly boxes for Alaska seafood

The fish-box project is supported by a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The UAA team has partners on the Kenai Peninsula, including the Center for Alaskan Coastal Studies and seafood companies like Kachemak Bay Shellfish Growers Co-Op and Salmon Sisters.

The seafood industry partners are enthusiastic, said Alex Ravelo, a University of Alaska Fairbanks postgraduate researcher working on the project.

“Nobody likes Styrofoam. That’s the reality. Everybody’s well aware of how bad it is for the environment,” she said.

Results from a test conducted over the past winter and spring are promising.

All but one arrived safely and sufficiently chilled, according to federal safety standards. The exception was the shipment to Florida, which was delayed for three days after it was accidentally left on the hot tarmac.

The MyghtyBox project has yet to reach any kind of commercial stage. As of early summer, the number of constructed boxes totaled only about 30, Amstislavski said. Scaling up production is a challenge yet to be cracked.

Home insulation possibilities

The fish-box project is part of a larger mycelium-cellulose vision.

Building new homes in rural Alaska is especially difficult because materials must travel over long distances to be used during short summer construction seasons. If materials don’t arrive in time, construction activities can be delayed for a full year.

Mycelium-based board could be a cheaper, faster-delivered, more convenient and higher-quality building material. In partnership with Amstislavski’s team, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory is investigating the possibility.

NREL researchers, operating at their site on the edge of the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus, have been testing different blends of cellulose-mycelium insulation.

There, at the site on the Cold Climate Housing Research Center campus, a mock cabin was set up as a mobile test lab, with panels of mycelium board of varying thicknesses, along with a section of currently used plastic insulation that served as a control. Performance has been measured at each of the panels.

Mycelium insulation could also address a quality problem that plagues Alaska homes, and particularly those in rural areas, where homes are old and weather-beaten: mold. The materials used widely in the Lower 48 can fare poorly in Alaska’s climate, Davis said.

“If you put two inches of foam around any house in Alaska, you’re going to create prime conditions for mold,” she said. “That’s wrecking a good percentage of homes in rural Alaska.”

Unlike plastic foam, which traps moisture, mycelium insulation can be breathable, she said.

The result of the NREL experiment are now being analyzed.

Interest in mushrooms began in the Russian Arctic

For Amstislavski, the journey to the Alaska cellulose-mycelium project has been something of a circle covering wide geographic and cultural distances.

He grew up in Russia, where his fishery biologist father worked in the Nenets region in theEuropean Arctic. There, as a young boy, he was immersed in Indigenous Nenets culture, which includes mushroom harvesting. There, mushroom harvesting is not just a pastime, but an important subsistence activity, especially in Soviet times, when other foods were scarce.

“I was lucky enough to be in a place with people who understood the landscape and the world, in a deeper, introspective way,” he said.

Amstislavski then earned a master’s degree from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, where one of his mentors was Tom Siccama, an expert in fungi. “He knew everything about North American mushrooms,” he said.

He then got a Ph.D. in environmental sciences from the City University of New York and taught for a while at the State University of New York before being lured to Alaska. That happened when he presented his research at a circumpolar conference in Fairbanks in 2012, which led to a job as a state public health manager, a position involving travel to rural villages. He came to UAA in 2014, a position that enabled him to study in Finland in 2021 on a Fulbright scholarship.

Amstislavski and his team members are not the only researchers looking at fungus as a solution to plastic problems.

Oyster farmers in Maine, for example, have experimented with buoys made of mycelium. British fashion designer Stella McCartney in 2021 unveiled some faux-leather productscrafted from mycelium. A Seattle company is developing a variety of products, from foods to construction materials, out of mycelium.

Alaska challenges

While mycelium development proceeds elsewhere, Alaska projects have some obstacles.

The University of Alaska does not have the type of well-connected business incubatorsthat exist at universities like Harvard, though UAF’s Center for Innovation, Commercialization, and Entrepreneurship has supported the mycelium research.

Alaska, with its remote location and high shipping costs, lacks the type of well-developed manufacturing capacity that exists in most states. Manufacturing in Alaska is dominated by seafood processing, which provides about two-thirds of the sector’s employment, according to the state Department of Labor and Workforce Development.

A new challenge comes from Trump administration decisions to axe funding for environmental research and climate change work.

The $2.5 million U.S. Department of Energy grant awarded in 2023 for the building-insulation project at NREL will not be renewed, the team recently learned.

Funding for NOAA has been drastically cut, though impacts to its marine debris programs and services are yet to be determined.

The Trump administration has resisted attempts to curb plastic pollution, most recently putting up roadblocks that led to the collapse of negotiations on an international plastics treaty.

Amstislavski hopes that entities beyond the federal government, including the private sector, will step in to support mycelium product development.

Aside from its environmental benefits, mycelium could help build Alaska’s workforce, a subject of concern for state officials, he said.

“It’s an opportunity for interesting jobs that are meaningful to people that have positive impacts in the world,” he said.