From Ocean To Arches; How Alaska's Pollock Ends Up In A Bun With Mayonnaise & Cheese

THIS IS AN EXCERPT CLICK HERE TO READ COMPLETE REPORT IN THE LEVER Deadly Harvest: The Hidden Costs Of Your Filet-Of Fish While the dee...

This article was originally published in The Lever, an investigative newsroom. Subscribe to their free newsletter here.

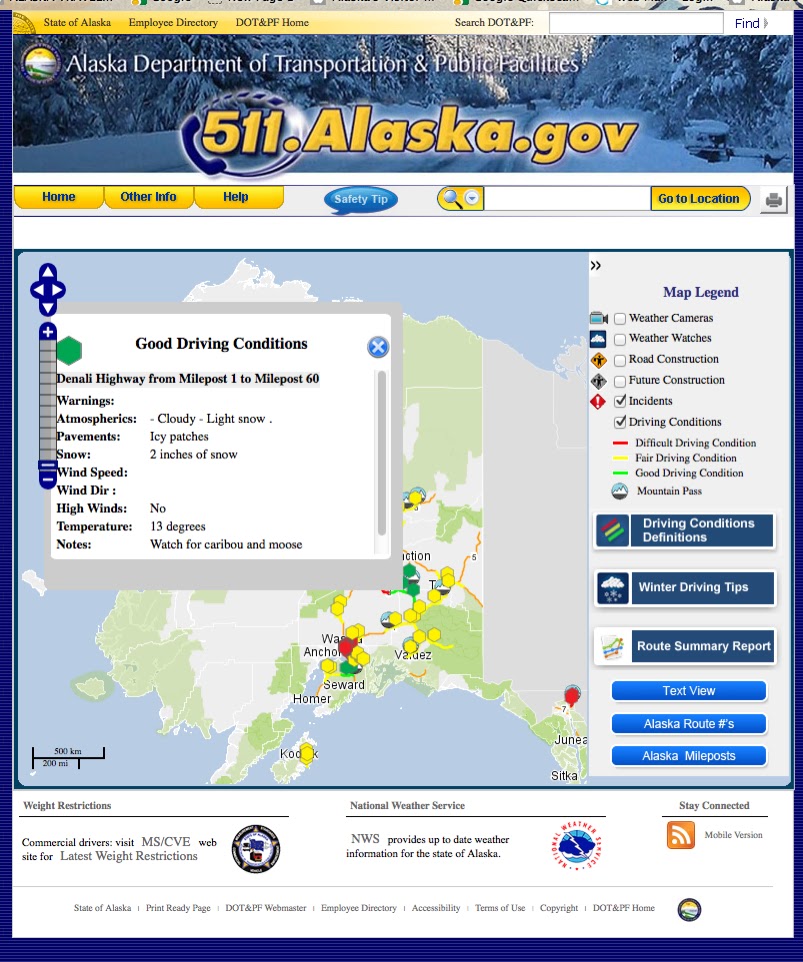

With a sizzle of grease, a McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish slides across the sticky drive-through counter in Homer, Alaska. Before being battered and fried, the fish in this sandwich was likely caught along the state’s rugged western coast, in the rapidly warming Bering Sea.

You’ve probably eaten Alaskan pollock, even if you didn’t know it—it’s in fish sticks in school lunches and freezer aisles, sold at Burger King, Wendy’s, Arby’s, and White Castle, mixed into fish-oil supplements, imitation crab meats, and faux salmon dips. Over 2.7 billion pounds of the mottled silver fish are caught annually in one of the world’s most valuable fisheries, representing a market of almost two billion dollars.

While pollock is often held up as a prime example of sustainably sourced seafood—industry groups claim it is “one of the most climate-friendly proteins in the world”—the reality is far more murky.

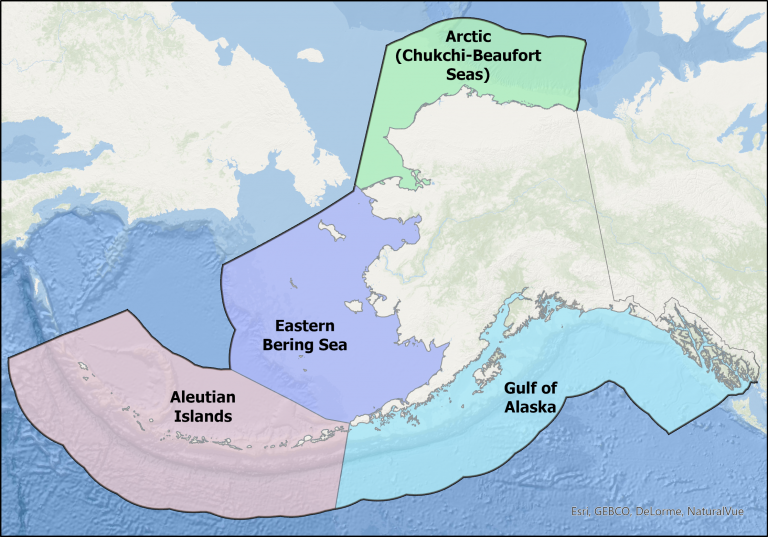

To get all this fish from the Bering Sea, which provides more than 40 percent of all seafood caught in the United States, factory trawlers drag huge nets that sweep up catches by the ton. Their gear regularlyscrapes the bottom of the seafloor for miles at a time, destroying vital, slow-growing habitat. Trawling boats—those that catch species living on the bottom, and those that target pollock—often snag species they don’t intend to, what’s known as bycatch. Regulators reported this included 10 orca whales in the Bering Sea last year.

Trawlers’ bycatch also includes failing fisheries like Chinook salmon—whose population has declined so much that residents on the Yukon River who rely on them are prohibited from catching any for the next seven years. Critics warn that years of disrupting marine habitat and food webs have contributed to massive population collapses in other species like seals and crabs. “They’re destroying the building blocks of the entire ecosystem,” says Kevin Whitworth, the executive director for Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, a group representing 33 federally recognized tribes along the Kuskokwim River.

Advocates say regulators are ignoring the mounting catastrophe, in part because many members of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, the federal body that oversees the Bering Sea’s fisheries, have close ties to—and in some cases simultaneously work for—the commercial fleets they manage. Smaller-scale fishermen, lawmakers, and tribal governments say the system is designed to protect the industry’s status quo.

A recent lawsuit against the council claims the regulatory body ignores well-conducted, peer-reviewed studies about trawling’s impacts on the Bering Sea floor, which stretches between Russia’s Siberian coast and Alaska’s Aleutian islands. Meanwhile, trawlers receive tax credits for funding research that helps shape council decisions. Even basic information like how often the fleet’s gear is making contact with the bottom has been overlooked, obscuring potential causes for species’ declines.

The council, and several of its members, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

|

| A map of Alaska’s four ocean regions.(National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) The trawl industry has aggressively pushed back against criticism, reportedly intimidating fishermen and journalists from speaking out for fear of losing jobs or limiting access to markets. Multiple people, including former council members, spoke to The Lever on condition of anonymity, citing previous personal threats. The Alaska Pollock Fishery Alliance, which represents the region’s pollock companies, told The Lever these fears are “unfounded.” Even as the climate has rapidly changed, putting stress on the marine ecosystem, government regulators have been slow to update harvest or bycatch limits for commercial fisheries. Now, two tribal groups are suing the federal government over its use of outdated 20-year-old assessments for its catch limits. As halibut populations shrink, for example, trawling vessels—primarily in the fleets that target species on the bottom—are allowed to accidentally catch and discard more halibut than sport and subsistence fishermen intentionally harvest. This gives industry “no incentive to reduce halibut mortality,” dozens of state legislators wrote in a recent bipartisan letter. After years of pleading by Alaskan residents worried about the obvious decline of other fish stocks, the council finally adopted an amendment tying how much halibut bycatch trawlers can sweep up to the fish’s relative abundance. Because this might restrict their fishing, trawlers promptly sued; the case is currently making its way through the federal court system. |

Meanwhile, trawlers are still hauling in bycatch. At the end of September, pollock trawlers based out of Kodiak, Alaska, accidentally caught around 12,000 Chinook salmon—almost the same amount that made it back to Canada last year. The ships were fishing in the Gulf of Alaska, but using the same kind of nets as they do farther north in the Bering Sea. The discovery prompted federal managers to shut down the fleet’s operations a month before it normally stops for the winter.

For Eva Burk, a Dene’ Athabascan who sits on a nonvoting advisory panel to the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, it feels like the deep-pocketed trawling industry, which is largely based in Washington, is getting a free pass, while tribal residents in Alaska are losing access to their traditional foods. “When you can’t fish, but other people are intercepting your fish, that is not sharing the burden of conservation,” she says.

Sitting in her kitchen in Fairbanks this spring, Burk was preparing smoked sockeye salmon, her hands swiftly packing cherry-red strips into jars. She’s had to modify her traditional recipes since the moratorium on catching the Yukon’s Chinook salmon, which threatens not only food security, but a crucial link to a way of life.

Her practiced gestures sharpen with frustration as she explains that for decades, residents have been sounding the alarm that Chinook were dwindling, not growing as large, and carrying fewer eggs. When fish navigate the turbulent waters of Alaska’s rivers, they are generally managed by the state, which has its own strained relationship with tribal residents. But salmon mature in the Bering Sea, where the waters between three and 200 miles offshore are regulated by the federal North Pacific Fishery Management Council. This fragmented system is a “super toxic, unhealthy space that’s dominated by economic interests,” Burk says.

As a result, “it’s not just the salmon that are in decline in my area,” she says. “It is everything, freshwater fish, migratory birds—everything.” But as a member on the council’s advisory panel, it’s been difficult for Burk to share traditional knowledge about how Alaska’s ocean and rivers are changing, like how baselines have shifted—or perspectives that don’t prioritize profits. “There’s just so much pressure on this resource,” she says. “I don’t know how to cure American capitalism, and that’s what this whole process needs.”