Repeating Disasters: Do People Listen To Warnings From The Past?

THE SANDS OF TIME Can We Speak Effectively To The Future? ...Maybe Not October 8th, 2024 It's a harsh time right now. Nature is givin...

https://www.countryjournal2020.com/2024/10/repeating-disasters-do-people-listen-to.html

THE SANDS OF TIME

Can We Speak Effectively To The Future?

...Maybe Not

October 8th, 2024

It's a harsh time right now. Nature is giving humans a message about its powers.

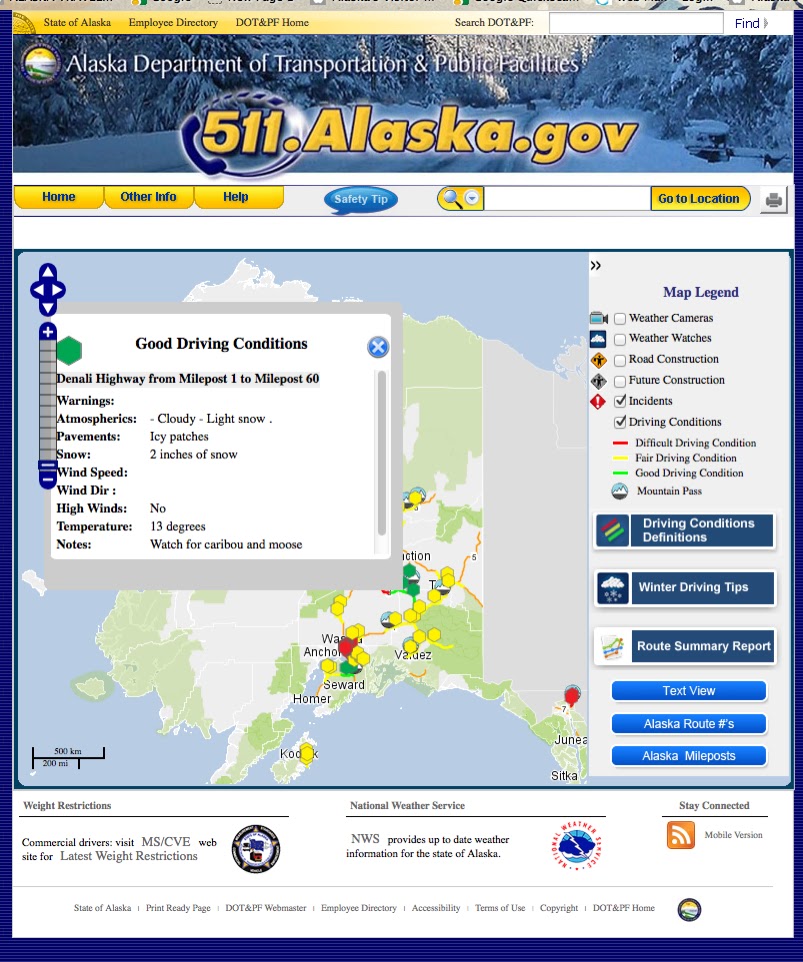

Massive hurricanes are bearing down on the Southern coast. Landslides have hit almost every town in the Alaska Panhandle in the past few years: Ketchikan, Haines, Wrangell, Juneau, Sitka.

•••

In 1921 – over 100 years ago – there was an 11-foot storm surge in Tampa, Florida. Salt water came up into the Florida citrus fields, poisoning the soil. There were 120 mph winds.

Not much later, in 1936 – in Juneau, Alaska – there was a massive mud landslide that filled up the streets.

You can find accurate stories of both these traumatic incidents – the one in Tampa and the one in Juneau – on the web.

It does seem like listening to what happened in the past is important. But we humans are optimists. And optimism can have its drawbacks. Basically, we don't want to hear it.

|

| The 1936 Juneau landslide brought truck-high mud right into the center of town. (Trevor Davis/ Alaska State Library Historical Collection) |

Here's a Journal story about two places – Japan and Alaska – where the people who lived in the past tried (and failed) to talk to us – the people of the future – about natural dangers.

COPPER RIVER COUNTRY JOURNAL

Everybody Tries To Give Wise Advice To Those Who Follow Us – But Does It Ever Work?

Lessons from the past: Tsunamis in Japan, Carved Stones, Lake Ahtna, the End of the Ice Age, and Warnings of the Dena'ina People

“Those that fail to learn from history are

doomed to repeat it.” -- Winston Churchill

Human beings never change throughout the ages. There are cautious people, and there are imprudent people

The world never changes either. It's always dangerous.

The world never changes either. It's always dangerous.

The people of our world learn tough lessons from nature. As we grow older, we have a desire to talk to our descendants; to warn them of what we've learned so they can avoid it.

But... does that work? Often, no.

LESSONS TO THE FUTURE IN JAPAN

Along the coast of Japan, there are hundreds of "tsunami stones" — some several yards tall. They look like tombstones – set back in the woods along the northern shore of Japan to mark the edge of inbound tidal waves that date back for six centuries.

The stones were erected there by the cautious. By those who wanted to keep their future generations safe. Who wanted to speak to them across the ages. They thought this would be a reliable and permanent system that would be hard to miss.

The stones were erected there by the cautious. By those who wanted to keep their future generations safe. Who wanted to speak to them across the ages. They thought this would be a reliable and permanent system that would be hard to miss.

Some of the stones were erected right before the Alaska Gold Rush, in 1896, when a huge tidal wave in Japan killed almost 30,000 people – washing up the hills to the exact point where the inscribed stones now stand.

The Japanese who lived a century ago tasked themselves with talking to their descendants through these stones. They chiseled indestructable messages, warning them not to build their homes between the stones and the sea. They also used a place-naming system to tell a story of woe and drive in that warning to the future. They shorthanded the stories so you couldn't miss them, calling places "Valley of the Survivors" and "Wave's Edge".

The Japanese who lived a century ago tasked themselves with talking to their descendants through these stones. They chiseled indestructable messages, warning them not to build their homes between the stones and the sea. They also used a place-naming system to tell a story of woe and drive in that warning to the future. They shorthanded the stories so you couldn't miss them, calling places "Valley of the Survivors" and "Wave's Edge".

Through stones and words, the Japanese wanted a simple way to telegraph their desperate message to the people who would be born centuries later and who might not understand the dangers of the ocean. Their motivation? To use their knowledge to save their great-grandchildren's lives.

But the people of the future tend to be imprudent. In Japan, they did not follow the warnings on the stones that were so carefully crafted and left for them, generations before, like a road map to safety.

LESSONS TO THE FUTURE IN ALASKA

The Copper Valley's water posed a hidden, longstanding danger. When the 1964 Earthquake occurred, Turnagain's ground turned to jello, and the big fancy homes that were on top of that lake-bottom water, still there after all these years, slid down a little slope – and right into the ocean. You can still see sections of concrete slabs and rebar at an angle along the shore when you walk the Coastal Trail.

The place called "Wave's Edge" – far from the shoreline – was meant to say:

“This spot – right here – was the edge of the huge wave that killed our families. Take care in the future! Don’t underestimate the danger. And don't put your house between this rock and the ocean."

But the people of the future tend to be imprudent. In Japan, they did not follow the warnings on the stones that were so carefully crafted and left for them, generations before, like a road map to safety.

They thought they knew better. They built within the Japanese tidal wave zone, below the rocks, and thousands of them were killed in the 2011 tsunami.

LESSONS TO THE FUTURE IN ALASKA

This idea of "speaking to the future" is a common yearning in many cultures, including for the Dena’ina people who lived near what was to become Anchorage.

After Alaska's largest city was established on Ship Creek, and money began to flow, incoming residents began building homes at a place along the shoreline, in a small, ill-defined upscale community which they called "Turnagain" – in honor of Captain James Cook's need to turn his ship again when he couldn't find a passage through the Kenai Peninsula.

When they renamed it with a Western naming system, the original Dena'ina name for that place was forgotten. Which is a shame. Athabascan names for places are practical and descriptive. They're useful and often tied to the land and geography.

Unknown to the people who chose to live in Turnagain in modern times, the expensive, homes in that refuge from the low-brow rest of Anchorage were built along the ocean on land that was capable, with a bit of shaking, of turning into soft, colloidal, semi-liquid soil.

Recently, scientists have come to believe that the instability of the land in Turnagain in Anchorage – that special, weird dirt under all those expensive homes – is our dirt. That it's dirt from the Copper River Valley.

They believe that Copper Valley sand was dumped in faraway Turnagain in Anchorage by the big Lake Atna megaflood at the end of the Ice Age. The flood occurred when ice dams melted 10,000 years ago and Lake Atna (ordinary folks would call it "Lake Ahtna") was freed from its icy bonds, and gushed and splashed enormous quantities of ice water through all the mountain passes out of the valley when the ice dams melted.

Lake Atna had been the defining lake of the Copper Valley. Researchers think the flood brought huge amounts of unexpected and unstable fresh water into the salty sea from the lake bottom – to this very spot on Cook Inlet.

By happenstance, the homes at Turnagain were "right at the mouth of where the flood came down," said Michael Wiedmer, who was studying the Lake Atna flood in 2011.

The Copper Valley's water posed a hidden, longstanding danger. When the 1964 Earthquake occurred, Turnagain's ground turned to jello, and the big fancy homes that were on top of that lake-bottom water, still there after all these years, slid down a little slope – and right into the ocean. You can still see sections of concrete slabs and rebar at an angle along the shore when you walk the Coastal Trail.

•••

The instability of the land at Turnagain wouldn't have surprised the Dena'ina people.The Dena'ina Athabascans knew all about that place and what was wrong with it, long, long ago.

The Dena'ina used language to explain the problem of Turnagain – just as the older Japanese who knew about their coastline in Japan and its problems used language on their carved stones and place names to try to help their descendents not get killed by tidal waves.

The Dena'ina called the unreliable land at Turnagain – the spot where new "Alaskans" rushed to build their fancy, big, earthquake-doomed homes – a very fitting name.

They called Turnagain "Rotten Land."