Battle Up North For Salmon Management

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON https://alaskabeacon.com/ Alaska Natives, barred from king salmon fishing, fight for their right to manage the Yuko...

FROM THE ALASKA BEACON

https://alaskabeacon.com/

Alaska Natives, barred from king salmon fishing, fight for their right to manage the Yukon River

Before government intervention, Native stewardship maintained salmon stocks since time immemorial, providing physical and spiritual nourishment

As a little girl growing up just south of the Arctic Circle in Alaska, Mackenzie Englishoe understood that her Gwich’in people and salmon were intrinsically connected. Salmon was the conduit of her first childhood lessons: Never take more than what you need; if you respect the salmon this year, they will come back the next.

Englishoe, now 22, described the salmon as “good medicine.” The fish protect Alaska Native people from diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Salmon comprises two-thirds of the food supply in Gwichyaa Zhee, also known as Fort Yukon, which sits adjacent to the Yukon River. More than physical sustenance, salmon is spiritual food.

But by the time Englishoe moved permanently to her ancestral land after completing school in Fairbanks, her chance to fish had already passed. There were so few salmon in her part of the Yukon that the state closed fishing.

“It hurt the deepest parts of me,” said Englishoe, who is also part of the Arctic Youth Ambassadors, a program run by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the U.S. Department of State. In 2023, she was selected as an emerging leader by the Tanana Chiefs Conference (TCC), a tribal consortium and nonprofit organization serving tribes in Interior Alaska.

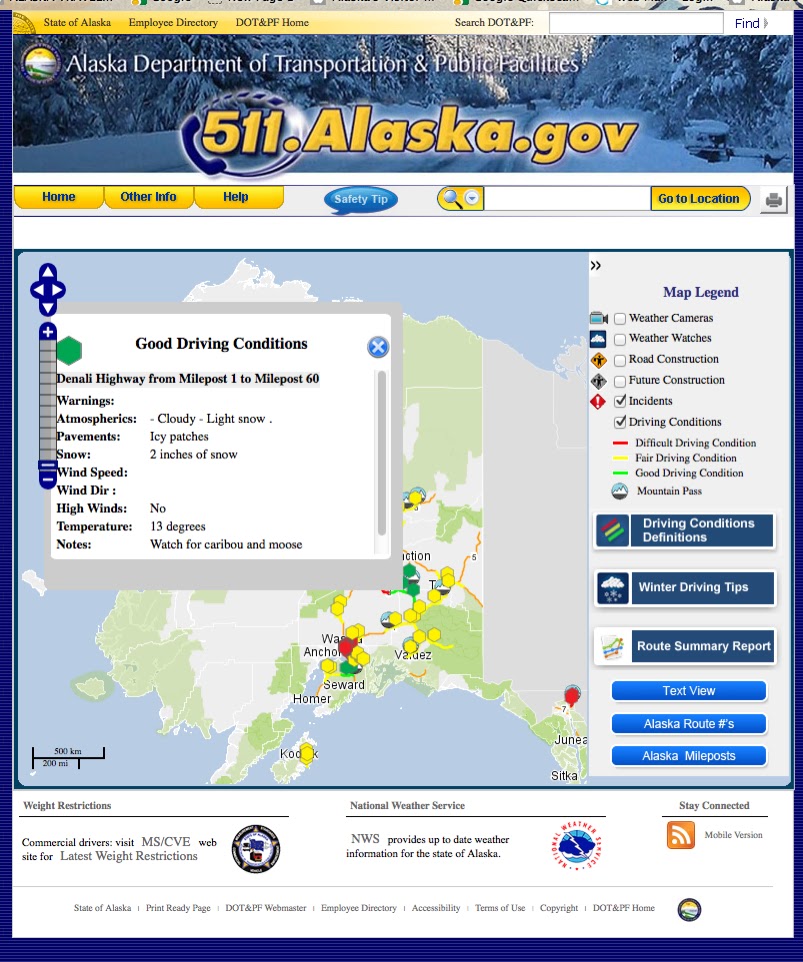

Indigenous peoples first reported concerns about the salmon run 60 years prior, after seeing drops in salmon numbers and sizes. The crash intensified in 2000, plummeted in 2019, and was so severe by 2024 that Alaska state managers and First Nations in Canada signed an agreement to close fishing for all Chinook, or king salmon, on the Yukon River for seven years. The fishing moratorium was set to span the life cycle of the Chinook salmon, named for an Indigenous tribe along the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest. It is also called king salmon for its size, reaching up to 5 feet long and 130 pounds.

Englishoe’s village of Gwichyaa Zhee is home to about 500 people, the second-largest along the Yukon. Part of the Yukon Flats, the region about the size of Maryland extends to the Canadian border. Residents throughout the Yukon Flats depend on salmon to make up the vast majority of their food supply, according to Alaska Department of Fish & Game (ADF&G) Subsistence Chief Caroline Brown.

But “the salmon can’t provide for us right now, so we have to let them go by,” Englishoe said.

The Yukon Flats represents a small subset of the Yukon River, which is home to more than 50 Indigenous communities, many of whom are hundreds of miles from the road system. The river spans 2,000 miles and two countries, and the land is home to multiple languages, distinct management structures, and varied access to other food resources. Upriver, First Nations in Canada, who are granted autonomy over management by the government, haven’t fished for decades. Downriver, Alaska Natives historically had access to additional salmon stocks on the Yukon, but the total closure of Chinook salmon fishing is devastating. The state of Alaska manages fishing within state boundaries. Commercial fishing in the ocean is federally regulated. While U.S. federal law prioritizes subsistence, Alaska’s state law does not.

Alaska Natives, whose Indigenous practices were banned by U.S. federal laws for generations, continue to face colonial policies that eradicate their culture. Subsistence king salmon fishing is cut off on the Yukon, while commercial fishing continues in the ocean. Policymakers are also largely ignoring the Indigenous stewardship practices that have kept salmon stocks thriving since time immemorial. The combination of state and federal policies prioritizes commercial fishing while subjugating Indigenous stewardship. Englishoe and other Alaska Natives along the Yukon, including Jody Potts-Joseph and Karma Ulvi in Eagle Village, are now fighting for the right to manage the river and save the remaining salmon stocks for future generations, before their way of life dies off with the salmon.

“We’re linked and tied to the salmon”

About 50 miles upriver from Englishoe, Potts-Joseph can feel the absence of salmon in her bones.

For generations, Potts-Joseph and her ancestors have looked to the Yukon and its salmon to provide key nutrients, including vitamin D, which sustains them through the long, dark winters, and fatty oils to lubricate their joints on dog sled runs to visit trap lines and gather firewood.

Potts-Joseph is a long-distance musher in Eagle Village, another part of the Yukon Flats, which is 6 miles from the Canadian border and 50 miles south of the Arctic Circle. She said mushing is her personal path toward cultural preservation, a way to honor her ancestors and her cultural connection to the land. Alaska Natives have used dogsleds in winter for generations, and still do. But the salmon crash has also made it more difficult to feed dog teams, which traditionally ate chum salmon, sometimes called dog salmon.

“We’re linked and tied to the salmon,” Potts-Joseph said. “It’s a big part of our culture and our society and family relations.”

In Eagle, 80% to 90% of the 2017 subsistence harvest was salmon, according to a study by Brown, the ADF&G subsistence chief, and Brooke McDavid of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

The salmon crash is already causing health problems for the Alaska Native peoples who rely on salmon to feed their communities.

Alaska Natives living along the Yukon faced a 70% increase in prediabetes, a 50% increase in malnutrition, and a 25% increase in diabetes after the salmon collapse, according to data collected by the TCC.

“There’s a lot of health implications of not having the king salmon in our diet because that’s when we get a lot of our nutrients. As Indigenous people, our DNA is … used to these kinds of traditional foods,” Potts-Joseph told Prism.

Alaska Natives living along the Yukon faced a 70% increase in prediabetes, a 50% increase in malnutrition, and a 25% increase in diabetes after the salmon collapse, according to data collected by the TCC. Research also shows salmon has protected Indigenous peoples from cancer and improves glucose tolerance.

“Normally, we would eat salmon two, three times a week all winter long, and now we don’t have any,” Potts-Joseph said while preparing a pot of moose and rice on the stove in her Eagle Village cabin. To combat food insecurity amid the salmon decline, some Alaska Natives are forced to turn to store-bought food to supplement their diets—and the expense is substantial. Food must be flown in by air cargo, costing 60 cents per pound for those in Fort Yukon and 73 cents per pound for those in Eagle. A trip to a major grocery store from Eagle in winter would also require a $320 airplane ticket.

“Part of their confidence”

Potts-Joseph reflected on the cultural loss of the salmon during a walk between her home and her parents’ house in February. She said her mother belongs to the generation of Alaska Native children who were sent to boarding schools. Alaska Native families are still healing from the colonial violence of that forced assimilation under the guise of education. Compounding that harm is the loss of culture threatened by both the decline in salmon populations and the government’s refusal to allow Alaska Natives to practice their foodways.

From 1891 to 1969, the U.S. operated boarding schools with laws mandating the removal of Native American children from their families. Children as young as 6 years old were sent to boarding schools many miles from home. Alaska Native children were called by a number instead of their name, and they were beaten for speaking their own language. Nationwide, at least 973 Native American children died while attending the schools, according to an investigation by the U.S. Department of the Interior that concluded in 2024. The youngest among Alaska Natives who were sent to boarding schools are now in their 60s.

“It’s just so important for us to hold onto our culture in any way possible,” Potts-Joseph said, her boots crunching into the snow shimmering in the sunlight as she made her way toward a set of cabins.

Eagle has a self-sustaining economy with service industries, a general store and hotel, solar power plants, a wellness center, and an emergency medical service, said Ulvi, the Eagle Village chief.

Potts-Joseph raised her now-adult children before the salmon collapse, imparting traditional knowledge, skills, and generational values.

“That’s a part of their confidence. That’s a part of their self-worth. They know where they come from and what they, as just a young kid, can contribute,” she said.

Englishoe said the loss of salmon left a void for young people, because their summers were dedicated to fishing.

She remembers a time of salmon abundance as a young girl when her great-grandmother, Mariam James, gave her an entire bag of dried salmon skins, her favorite food and a treat that she always looked forward to when seeing them. James taught Englishoe to honor her relationship with the salmon, and now Englishoe’s ability to honor ancestors is lost with the salmon.

At funeral potlatches, which were banned by colonial laws for generations, salmon ceremonially sends the deceased into the afterlife. Holding funeral potlatches without salmon is a double loss to grieve.

A long battle

A combination of factors is contributing to the salmon decline. The ecosystem is transforming due to climate change, with rising water temperatures harming the cold-water fish and melting permafrost and sea ice altering the river’s composition. Other factors include increased competition with hatchery fish, commercial salmon fishing, bycatch (or salmon caught accidentally by pollock trawl fishers), and a fish disease called ichthyophoniasis, which plagues Yukon Chinook salmon in particular and is exacerbated by warmer waters.

“It’s all of those things happening simultaneously and unpredictably, because they interact with each other,” said Bathsheba Demuth, an environmental historian and professor at Brown University who has spent five years researching her book on Yukon River history.

The seven-year moratorium on fishing also established the Yukon River Panel, made up of 12 people from the U.S. and Canada, tasked with developing a comprehensive rebuilding plan for Chinook salmon.

The Alaska Salmon Research Task Force, established by an act of Congress in 2022, released a final report in 2024 identifying research gaps and priorities to address the salmon collapse. It recommended incorporating Indigenous knowledge into research examining the salmon life cycle in both the ocean and freshwater environments.

Any potential progress was halted when President Donald Trump signed executive orders to expand commercial fisheries and decrease marine protections, cutting funding for Alaska fisheries management and research. This cut included the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, which manages bycatch limits. The council did not respond to multiple interview requests.

When we’re talking about the food that we’ve relied on for generations, for thousands of years, it’s hard to understand why our people aren’t involved at the table when we have the closest relationship to the salmon.

– Mackenzie Englishoe

The bycatch limit for Chinook salmon is 60,000, double the total subsistence harvest in 2012 (which was the largest harvest in more than a decade), according to data collected by the TCC. There is no bycatch limit on chum salmon, a stock that has also collapsed. Chinook and fall chum are the only salmon species to reach the Yukon headwaters. By 2021, the subsistence harvest had dropped to zero for both species, the TCC data shows.

Indigenous communities along the river are now asking state managers for rights to co-manage the river.

“When we’re talking about the food that we’ve relied on for generations, for thousands of years, it’s hard to understand why our people aren’t involved at the table when we have the closest relationship to [the salmon],” Englishoe said.

Scientists have proposed multiple models aimed at rebuilding salmon stocks, and none of them indicate it could be done in less than 50 years. Alaska Natives like Englishoe likely view the time span differently than Western scientists. Indigenous practices are centered on their impact on future generations, operating on a different timescale from colonial governments. Colonialism, with its individualistic values, forces capitalistic rules onto Indigenous cultures centered on communal benefit.

Englishoe is taking on the fight for the salmon, knowing that she is unlikely to see an end to the battle in her lifetime.

“This is a generational task. It’s not just mine,” she said. “It’s my turn, though.”

“The Yukon River has the right”

Before the salmon decline, during an August afternoon, Alaska Natives would have been sharing stories and salmon together at a fish camp. Following in the traditions of their nomadic ancestors, Alaska Natives built camps along the river where they spent long summer days catching and preparing fish under the midnight sun, smoking salmon for the winter and passing on traditions. Instead, on a recent August afternoon, some were gathered on a weekly conference call, known as the In-Season Salmon Management Teleconference,hosted by the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association. A woman on the call announced the progress of 12 Chinook salmon—10 males and two females—who were following their instincts 1,800 miles upstream on the Yukon River toward their spawning grounds, unaware their journey was a news item for an international audience.

Yukon River Chinook endure the longest migration of any salmon, traveling up to 2,000 miles upstream, the equivalent of swimming north to south along California’s coast twice. The salmon spend the majority of their adult lives in the Bering Sea, between Russia and Alaska, the base of operations for a $1.5 billion pollock industry. Salmon that survive to the end of their lifespan return to the Yukon to spawn, then die.

Salmon’s journey takes them through fisheries operated by the U.S. and Russia, through portions of the Yukon managed by the state of Alaska, and across the Canadian border, where First Nations manage the river.

“The regulatory tangle on the Yukon is so intense,” said Demuth, the environmental historian and university professor.

Land use agreements signed on each side of the border wildly differentiate the authority Alaska Natives and First Nations have over the river. First Nations are given autonomy to manage waterways in Canada, while Alaska law has no mandate to consult with Indigenous peoples in management, Demuth explained.

Demuth set off down the Yukon River in 2020, expecting to find lively fish camps all along the river, with kids running along the riverbank and people stopping by to visit and share news just as they did when she lived in Yukon Territory. Instead, she found them all empty.

Five years later, Englishoe said fish camps are deteriorating. The costs to maintain them cannot be justified when they are not being used to fish, and gas costs $11 per gallon.

“We can’t save those things anymore,” she said.

But Alaska Natives are determined to preserve their culture, and they are finding ways to do so.

“I’ll tell you what, the Gwitch’in are some tough people,” Potts-Joseph said. “We definitely won’t back down. We’ll continue to fight.”

Eagle Village hosted a culture camp in August aimed at preserving traditional skills, including fishing, language, and crafts. Ulvi, the Eagle Village Chief, told Prism a whitefish and a moose were used for demonstrations to pass on the skills from elders to young people. She also hosted gatherings for the village elders, and the TCC paid $2 million to provide salmon from commercial fisheries to its people.

An exception to the seven-year moratorium on Chinook fishing was added in June to allow for limited fishing for cultural and educational purposes. A representative of the Alaska Department of Fish & Game said during the August teleconference that they received a few applications after opening the program in June.

Still, Alaska Natives are calling on state decision-makers to take one simple step toward solving the salmon crisis: Listen to the Indigenous-led solutions.

“We have solutions, and they know what the solution is but they won’t do it because it’s money over anything,” Potts-Joseph said, referring to commercial fisheries and state managers.

Courtney Carothers is a professor of Fisheries and Ocean Science at the University of Fairbanks, where she is also part of the university’s Tamamta program, a graduate program that incorporates traditional knowledge into Western science. When it comes to fishery management in Alaska, Carothers said there is a chasm between the way state managers view salmon as a commodity and how Alaska Natives view salmon as a relative.

This resonated with Englishoe, who was told something by an elder on a recent trip to Whitehorse that she said she will never forget.

“He said, ‘Mother Nature will always provide for our needs, but never for our greeds,’” Englishoe recalled. “I think about that now every day.”

The Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association is advocating for Native rights to manage the Yukon River, looking to federal and tribal co-management of Alaska’s Kuskokwim River and the Alaska Migratory Birds Co-Management Council as guides. Englishoe wants to go a step further and obtain “personhood” for the Yukon.

“All across the Yukon, we all know how influential this river is to us. We’ve planned our entire lives around this river, and our travels, our stories. It’s carried our fish, our canoes,” she said.

“So I look to the river—I’m looking at it right now—and I think that the Yukon River has the right to stay clean. The Yukon River has a right to feed its Indigenous people. The Yukon River has a right to host its salmon on the longest salmon run in the world. The Yukon River has a right to feed its own animals and its land,” she said. “And this is something I’m going to be fighting for for the rest of my life.”

Editorial Team:

ray levy uyeda, Lead Editor

Tina Vasquez and Carolyn Copeland, Top Editors

Stephanie Harris, Copy Editor

Prism is an independent and nonprofit newsroom led by journalists of color. We report from the ground up and at the intersections of injustice.