NOAA Cuts To Affect Fisheries Management

NOAA firings, cuts will reduce services used to manage Alaska fisheries, officials say Scientists have scrambled to stage necessary fish s...

NOAA firings, cuts will reduce services used to manage Alaska fisheries, officials say

Scientists have scrambled to stage necessary fish surveys, but data analysis, salmon research and other services will be impacted, officials tell the North Pacific Fishery Management Council

Trump administration job cuts in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will result in less scientific information that is needed to set and oversee Alaska seafood harvests, agency officials have warned fishery managers.

Since January, the Alaska regional office of NOAA Fisheries, also called the National Marine Fisheries Service, has lost 28 employees, about a quarter of its workforce, said Jon Kurland, the agency’s Alaska director.

“This, of course, reduces our capacity in a pretty dramatic fashion, including core fishery management functions such as regulatory analysis and development, fishery permitting and quota management, information technology, and operations to support sustainable fisheries,” Kurland told the North Pacific Fishery Management Council on Thursday.

NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which has labs in Juneau’s Auke Bay and Kodiak, among other sites, has lost 51 employees since January, affecting 6% to 30% of its operations, said director Robert Foy, the center’s director. That was on top of some job losses and other “resource limitations” prior to January, Foy said.

“It certainly puts us in a situation where it is clear that we must cancel some of our work,” he told the council.

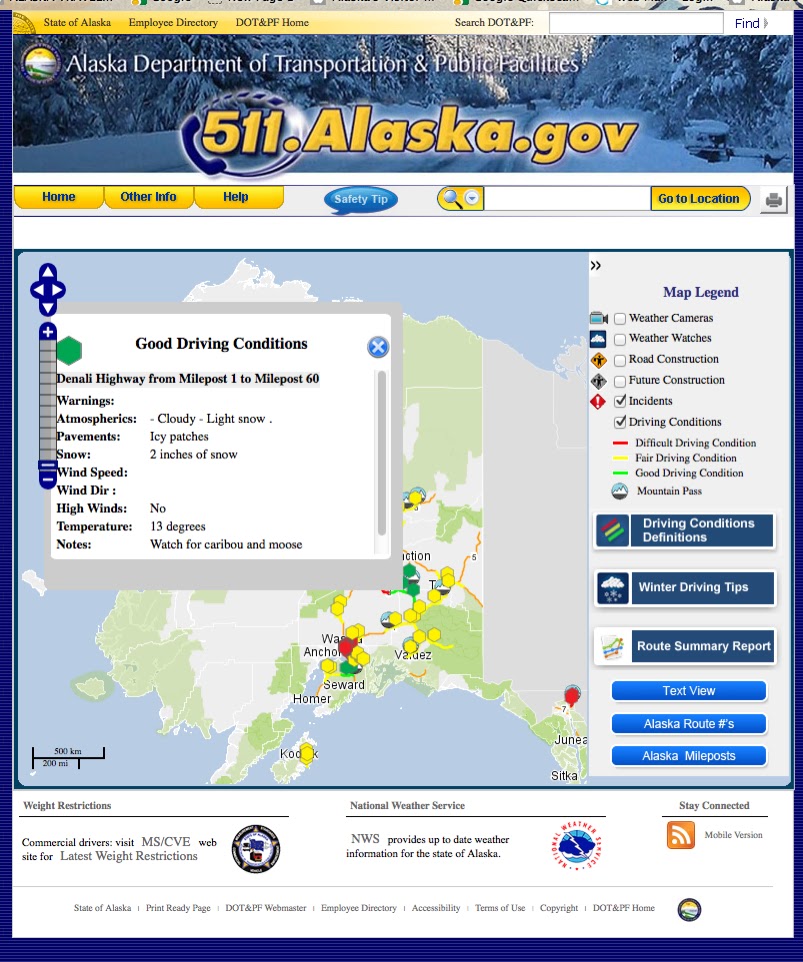

The North Pacific Fishery Management Council, meeting in Newport, Oregon, sets harvest levels and rules for commercial seafood harvests carried out in federal waters off Alaska. The council relies on scientific information from NOAA Fisheries and other government agencies.

NOAA has been one of the targets of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, which has been led by billionaire Elon Musk. The DOGE program has summarily fired thousands of employees in various government agencies, in accordance with goals articulated in a preelection report from the conservative Heritage Foundation called Project 2025.

NOAA’s science-focused operations are criticized in Project 2025. NOAA Fisheries, the National Weather Service and other NOAA divisions “form a colossal operation that has become one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry and, as such, is harmful to future U.S. prosperity,” the Project 2025 report said.

The DOGE-led firings and cuts leave Alaska with notably reduced NOAA Fisheries services, Kurland and Foy told council members.

Among the services now compromised is the information technology system that tracks catches during harvest seasons — information used to manage quotas and allocations. “We really have less than a skeleton crew at this point in our IT shop, so it’s a pretty severe constraint,” Kurland said.

Also compromised is the Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s ability to analyze ages of fish, which spend varying amounts of years growing in the ocean. The ability to gather such demographic information, an important factor used by managers to set harvest levels that are sustainable into the future, is down 40%, Foy said.

A lot of the center’s salmon research is now on hold as well.

For example, work at the Little Port Walter Research Station, the oldest year-round research station in Alaska, is now canceled, Foy said. “We’re talking about the importance of understanding what’s happening with salmon in the marine environment and its interaction with ground fish stocks,” he said.

As difficult as the losses have been, Kurland and Foy said they are bracing for even more cuts and trying to figure out how to narrow their focus on the top priorities.

Despite the challenges, Foy said, the Alaska Fisheries Science Center has managed to cobble together scheduled 2025 fish surveys in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, which produce the stock information needed to set annual harvest limits. Some of the employees doing that work have been pulled out of other operations to fill in for experienced researchers who have been lost, and data analysis from the fish surveys will be slower, he warned.

“You can’t lose 51 people and not have that impact,” he said.

It was far from a given that the surveys would happen this year, Foy said. The science center team had to endure a lot of confusion leading up to now, he said.

“We’ve had staff sitting in airports on Saturdays, not knowing if the contract was done to start a survey on a Monday,” he said.

Pressure for bigger harvests

At the same time the Trump administration is making deep cuts to science programs, it also is pushing fishery managers to increase total seafood harvests.

President Donald Trump on April 17 issued an executive order called “Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness” that seeks to overturn “restrictive catch limits” and “unburden our commercial fishermen from costly and inefficient regulation.”

Federal fishing laws, including the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, require careful management to keep fisheries sustainable into the future. Unregulated fisheries have collapsed in the past, leading to regional economic disasters.

Part of the impetus for the executive order, a senior NOAA official told the council, is the long-term decrease in overall seafood landings.

Prior to 2020, about 9.5 billion pounds of seafood was harvested commercially each year, said Sam Rauch, NOAA Fisheries’ deputy assistant administrator for regulatory programs. Now that total is down to about 8.5 billion pounds, Rauch said.

He acknowledged that the COVID-19 pandemic played a role in the reduction, as did economics.

At their Newport meeting, council members raised concerns that the push for increased production might clash with the practices of responsible management, especially if there is less information to prevent overharvesting.

The typical approach is to be cautious when information is scarce, she noted. “if we have increased uncertainty — which we’ll have with fewer surveys or fewer people on the water — then we usually have more risk, and we account for that by lowering catch,” she said at the meeting.

In response, Rauch cited a need to cut government spending in general and NOAA spending in particular. That includes the agency’s fishery science work, he said.

“We have to think about new and different ways to collect the data,” he said. “The executive order puts a fine point on developing new and innovative but also less expensive ways to collect the science.”

Even before this year, he said, NOAA was struggling with the increasing costs of its Alaska fish surveys and facing a need to economize.

The agency had already been working on a survey modernization program prior to the second Trump administration.

The Alaska portion of the program, announced last year, was intended to redesign fisheries surveys within five years to be more cost-effective and adaptive to changing environmental conditions.

Foy, in his testimony to the council, said job and budget cuts will now delay that modernization work.

“I can almost assuredly say that this is no longer a 5-year project but probably moving out and into the 6- or 7-year” range, he told the council.

Since Alaska accounts for about 60% of the volume of the nation’s commercial seafood catch, it is likely to have a big role in accomplishing the administration’s goals for increased production, council members noted.

Alaska’s total volume has been affected by a variety of forces in recent years. Those include two consecutive years of the Bering Sea snow crab fishery being canceled. That harvest had an allowable catch of 45 million pounds in the 2020-2021 season but wound up drastically reduced in the following year and shot down completely in the 2022-23 and 2023-2024 seasons because of a collapse in the stock.

Another factor is the shrinking size of harvested salmon.

Last year, Bristol Bay sockeye salmon were measured at the smallest size on record. The total 2024 Alaska salmon harvest of 101.2 million fish, one of the lowest totals in recent years, had a combined weight of about 450 million pounds.

Past years with similar sizes harvests by fish numbers yielded higher total weights. The 1987 Alaska salmon harvest of 96.6 million fish weighed a total 508.6 million pounds, while the 1988 Alaska salmon harvest of 100.6 million fish weighed in at 534.5 million pounds, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

View The Alaska Beacon Website: https://alaskabeacon.com/